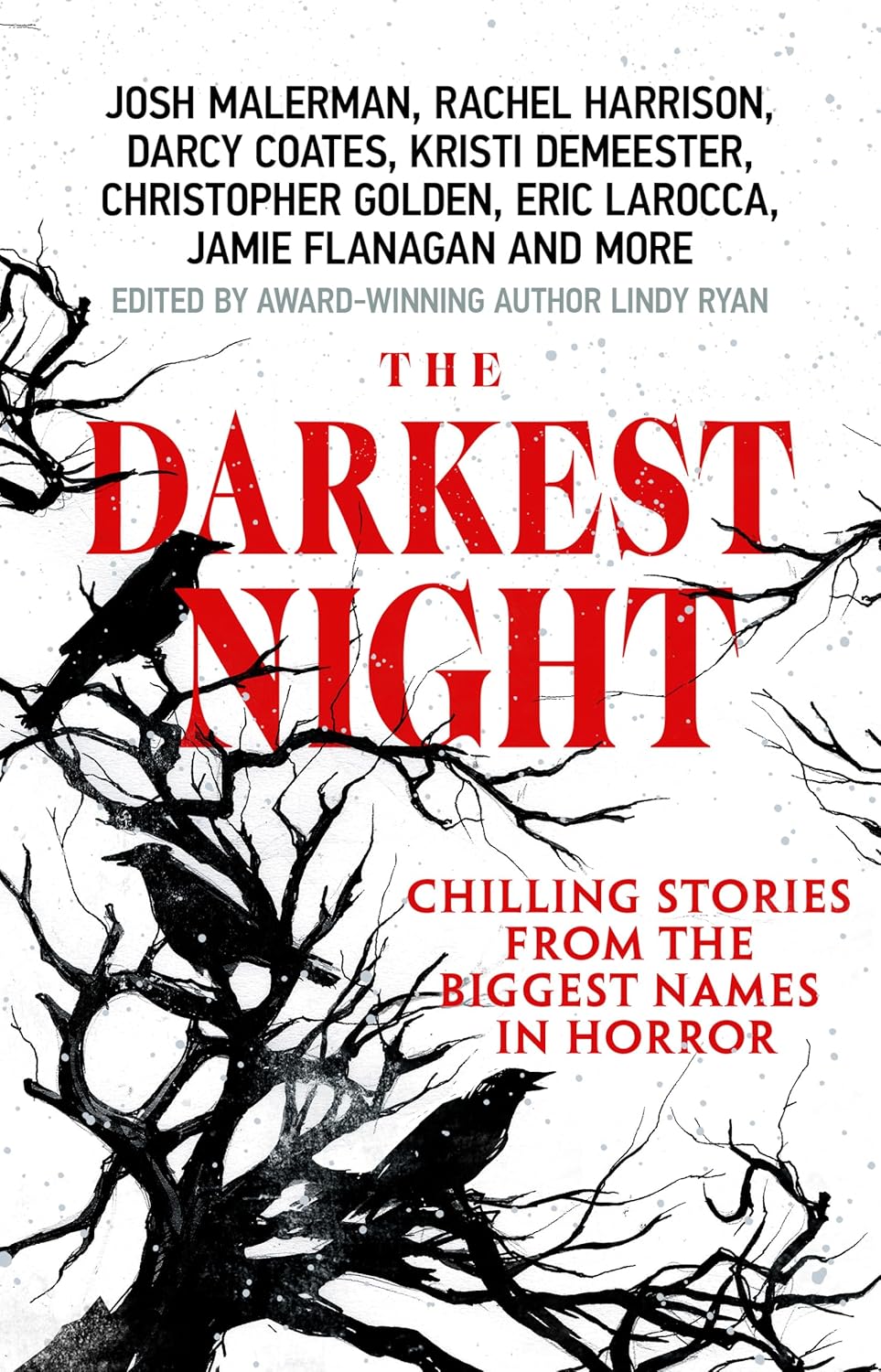

It seems counterintuitive that we become more receptive to scary stories as the days get shorter and the temperature drops—a time when we need security more than ever. We can argue that horror stories serve basic needs. They help us confront our fears while acting as vehicles for criticism and introspection. But the most important service they perform is to entertain without ignoring the darkness around us. And during the time of the year that many people find the most difficult, physically and emotionally, entertainment saves. Some versions of horror are chilling while others are kitsch. Some are beautiful while others are ridiculous. Editor Lindy Ryan’s anthology, The Darkest Night, houses a variety of these wonderful terrors from many prize-winning names in contemporary horror literature.

It seems counterintuitive that we become more receptive to scary stories as the days get shorter and the temperature drops—a time when we need security more than ever. We can argue that horror stories serve basic needs. They help us confront our fears while acting as vehicles for criticism and introspection. But the most important service they perform is to entertain without ignoring the darkness around us. And during the time of the year that many people find the most difficult, physically and emotionally, entertainment saves. Some versions of horror are chilling while others are kitsch. Some are beautiful while others are ridiculous. Editor Lindy Ryan’s anthology, The Darkest Night, houses a variety of these wonderful terrors from many prize-winning names in contemporary horror literature.

The opening story, “The Mouthless Body in the Lake” by Gwendolyn Kiste, is gripping from line one: “On Christmas morning, you discover your own body frozen beneath the ice in Lake Minton.” Like many doppelgänger stories, the protagonist’s fear of themself is on display. The mirror self being mouthless is a delightfully creepy detail indicating that the double is the silenced part of the protagonist. Kiste gives the story an even subtler twist in using second person narration. This makes readers both observer and main character, effectively doubling us: an invitation to reflect on the parts of ourselves that we’ve silenced. Is our mouthless double a demon or a victim? Should we free them or leave them frozen in the depths of our psyches?

Self-confrontation is a staple of fiction, but horror writers use it to follow an infinite number of narrative routes. “The Body of Leonora James” by Stephanie M. Wytovich follows the eponymous Leonora James, a revenant and a local legend who rises yearly to torture and drink the blood of young women. But someone else has learned how to harness her power against her. How should we feel when a monster becomes a victim? How satisfying is vengeful justice? More importantly, how dangerous is it? Clay McLeod Chapman’s story, “Mr. Butler,” turns that theme around. The protagonist is reunited with a magical, talking cardboard box that once protected him from his abusive stepfather. But now that he’s a father, why has it reappeared? To befriend his son? Is he now a victim or an abuser? Who is the hero in this story—the protagonist or his self-consuming conscience?

The twisted knots of family ties are everywhere in this anthology and Cynthia Pelayo’s “The Warmth of Snow” is a beautifully written example. The narrator is a young woman living with her mother who forbids her to fall in love. This kind of premise, in a modern setting, is extremely difficult to pull off, but I had no trouble suspending disbelief. Why? I can’t say. I can only assume Pelayo has infused her prose with some kind of fairy-tale witchery. The style is enchanting and it sets the tone brilliantly from the first lines.

Mother didn’t believe we should have a television, and so we didn’t. Mother also didn’t believe in love. She believed in cold and snow and mistletoe. She believed our hearts should hold still, unbeating, unflinching to the love of another.

[…]

I asked Mother again, “If we aren’t to believe in love, then what are we meant to believe?”

She didn’t look up from what she was reading. She turned the page and said: “You will love books. Turn to the books. You’ll find feeling and meaning in the books, or in the plays.” She lowered her voice. “And nothing else.”

This feels like Carrie written by the Brothers Grimm. Personally, I find the mother’s zealotry for books easy to identify with—this is a safe space for literature addicts. But in this dysfunctional family story, Pelayo takes readers’ tendency to overexaggerate literature’s role to an extreme that leads to horrible consequences. This story says—oh horror of horrors—that books can’t be everything to a fulfilling life, ironically using the art of storytelling to bring home questions of art’s limitations.

This anthology does, of course, have stories that won’t provoke an existential crisis for bookworms. Fans of gory kitsch will love Nat Cassidy and Jeff Strand’s respective stories about nice boys gone bad. Eric LaRocca’s velvet-toned Victorian pastiche, “I Hope This Finds You Well,” delves into the world of a gentlemen’s club and its members’ dark fetishes. Christopher Golden and Tim Lebbon’s “Wintry Blue” simultaneously explores the demons that lie within us while also serving up fantastic wendigo fight scenes. In Kelsea Yu’s “Carol of the Hells” neither the protagonist, Holly, nor her mother have recovered from the death of her father and brother. An abusive blame-game with nasty exchanges between mother and daughter leads them to horrible acts.

But Kristi DeMeester’s story, “Eggnog,” wins the Joan Collins prize for cattiest dialogue. Gillian is a new mother with body issues that are exacerbated when she meets her husband’s gorgeous co-worker, Elise, at the company Christmas party. Elise makes no secret of her designs on Gillian’s husband and the dialogue between the women is deliciously snippy: “And this sweater. So festive! I wish I could do wool, but it’s too thick. Makes me feel like a beast. Hulking around […] But it works for you. Shorter frame and all.” … I mean… Girl…

Gillian’s thoughts when she’s forced to go to the bathroom to express milk are a wonderful example of how to combine scene-setting with characterization.

[T]he wine-poisoned milk rushes out of me. Collects in the tiny bottles I’m meant to feed my baby but will instead dump down the toilet and flush.

Bitch-shh, bitch-shhh, bitch-shh.

Emotion and sound combine into an onomatopoeia of pearl-clutching shade. Will Gillian turn the other cheek? Of course not. But I’ve said enough and will reveal no more.

The Darkest Night has stories with guilt-racked parents, haunted children, revenge fantasies, creepy snowmen, snarky Santas and even plans for breaking into the Louvre. It’s doubtful that every piece in this collection will win you over, but the book shows the wonderful diversity of seasonal horror. These stories, blood-chilling though they are, will warm you up on the coldest winter nights.

Publisher: Crooked Lane Books

Publication date: September 24, 2024

Reviewed by David Lewis

David Lewis’s reviews and fiction have appeared or are forthcoming in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Joyland, Barrelhouse, Strange Horizons, The Weird Fiction Review, Ancillary Review of Books, 21st Century Ghost Stories Volume II, The Fish Anthology, Willesden Herald: New Short Stories 9, The Fairlight Book of Short Stories, Paris Lit Up and others. Originally from Oklahoma, he now lives in France with his husband and dog.