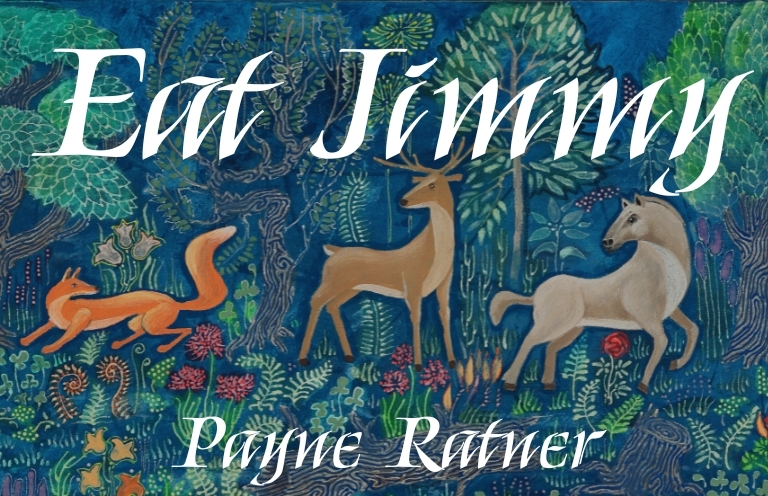

Payne Ratner’s “Eat Jimmy” is a strange and mesmerizing story. Like a Brothers Grimm fairy tale, young Jimmy is told by his mother that he’ll soon be eaten in order to save her. An evil stepfather, a talking dog, and an encounter with Jesus add to the world’s strangeness, making the emotional impact all the more real.

Just before bedtime, on Tuesday night, Jimmy’s mother told him the bad news.

“What do you mean?” Jimmy said.

He touched her cheek. Tears made her eyes grow big. She had the book of fairy tales in her lap.

“When?” he said.

“I don’t know. Sometime soon.”

“Why?”

“Because,” she said. She turned away from him and tears dropped on her forearms.

Jimmy looked at her hands. The fingers had grown cold and skinny and the tips of them hard and sharp.

Jimmy put up his hands and bent his fingers and said, “Grrrrrr.” He uncurled his fingers and said, “You can’t eat me. I’m a little boy.”

“You want me to die?” she said.

“No,” Jimmy said.

She licked a fingertip with her blue tongue.

“I’m just telling you now,” she said, “so you won’t be surprised.”

Then she started to read.

“Will it hurt?” Jimmy asked.

“I would never hurt you,” his mother said.

* * *

After she left Jimmy watched the moon. It slipped into his room and looked around for things it wanted after he was eaten.

* * *

In the morning his mother sat in front of the stove. A package of bacon, the plastic cloudy with grease, was on the floor beside the bone of her ankle. All the bacon meat bubbled in the iron skillet. His mother held a spatula in her lap.

“We missed the bus,” she said.

“That’s okay, I don’t like school.”

The phone rang.

“Bring me the phone, ‘kay?”

It was Dick. Jimmy could tell by the way she laughed.

“Kinda sorta,” she said, “not actually.”

Dick had thick black hair on his arms and under the hair was the tattoo of a dragon. When he flexed his muscle, the dragon lifted its green lip and revealed a tooth.

When Dick first started to come over, he brought thick white packages of meat soaked through in dark red in spots. Jimmy could put his finger through the soft red spots and touch the meat.

Dick would hand the packages to his mother and say, “We gotta fatten you up.”

Sometimes they’d visit Dick at the store. He worked in the meat department at Montello’s Supermarket. His Mom would press a silver button on the tile wall beside the glass case but there was no sound.

Jimmy’s father used to have a dog whistle. When he blew it, it didn’t make a sound either, but dogs of all kinds approached the house and stood and waited.

When his mother pressed the silver button there was no sound, but Dick came out.

He wore a long white coat with bloody faces all over it. He wore a metal case on his leg with knives in it.

Jimmy wanted to see the knives, but his mother said they were too dangerous. Then one day she said, “Oh, all right.”

One of Dick’s fingers was bit off by a war. He lost his job before this one, because his boss didn’t know his ass from a stick in the town.

There’s a truck that comes round the neighborhood, like the Popsicle Man truck in the summer, but it plays different kinds of music. Men and women come out of the house and stop the truck and the man comes into the back of it and marries them. That’s what happened to Dick and Jimmy’s mother. The man in the truck has rings in a case and gives them a bottle of fizz at the end and drives off but no ice cream.

* * *

While his mother gurbled into the phone, Jimmy got the box of Lucky Charms. He took them in front of the TV. Sesame Street was on.

He could hear his mother’s low laugh in between Oscar and Elmo. She laughed like that in her bedroom when Dick had a sleepover. Jimmy would lie down at the bedroom door and listen and smell what came out from the gap at the bottom of the door.

He came over more now that Jimmy’s mother was sick to make her well.

Jimmy could smell the bacon smoking. He went in, turned off the blue flame under the skillet.

“Come’re,” his mother said.

She held out her arms. He climbed in her lap. He could feel all her bones. She was like the jungle gym at school. The bones of her arms clamped around him. The big bone of her face rested on his shoulder.

Only her dark eyes were the same.

“You know how much I love you and I never ever would ever want to hurt you.”

Tears crawled around on her face like small bugs with bits of the room in their belly. He crushed them with his fingertip.

“Can we go to Joyland today,” Jimmy said.

“Not today, honey.”

* * *

The dog left a week ago. He stood on the front lawn and looked across the highway. You could see his ribs, and his tail hung down like dripped wax.

Then he walked back to Jimmy. Jimmy dug a hole in the dirt with a water glass. He was digging to the other side of the earth. At night the sun hides on the opposite side of the world and would like to stay there except men with long, sharp steel poles poke it to make it leave and come to the side where Jimmy lives.

He set down the glass and looked at the dog.

“You would be wise to come with me,” the dog said.

Jimmy looked in the warm eyes of the dog.

“I’m sorry about the cat,” the dog said, “I thought I was a goner.”

“That’s okay.”

Jimmy looked back at the hole. It was hard to dig because of all the stones in the earth. They were like locks.

When Jimmy looked up the dog had disappeared through the chinks in the traffic.

* * *

Jimmy found a fork in the sink and took the bacon out of the skillet. He ate six strips. Then he rinsed off the plate and rubbed it with a yellow sponge. Then he dried it and laid out the rest of the bacon in a pretty design. He poured the rest of the milk in a glass and he found that plastic flower behind the recliner, put it all on a tray and took it out to his mother.

Mister Rogers was on TV. His mother was asleep on the sofa. He could see her teeth. Her teeth had grown so big. Someday he would say, like the story, “My, what big teeth you have, Mother” and see if it made her laugh.

She had on one of Dad’s old T-shirts. Her legs were open, and she didn’t have underwear on. He looked at what he saw.

When he was born he came out of there and made his mother have the happiest day of her life.

He must have come out like a tiny silver button. His mother must’ve kept him warm in her mouth. Or maybe he was an egg. Or like a sour ball. And then he hatched, and he climbed out and hung on to her lower lip then dropped down to the floor and watched Quest for Camelot on TV. His mother said he watched it over and over.

In school several kids had disappeared. Then their parents came to talk to the class and read stories. Their faces were fat and red and about to burst.

“The old ways,” they said, “sometimes turn out to be the best ways.

The teacher started to cry. She pushed a handkerchief to her eyes.

“Careen,” Mister Victor said, “had three months to live. Now look at her.”

Careen got up and did a little circle in front of the class. She spun like a dancer and her dress floated up and you saw the little red blur of her underwear and her feet were like flickering fire.

Jimmy slid his mother’s medicine to the corner of the table. He was careful not to touch the needle because the needle, his mother said, would kill him.

He put his hand on the bone of his mother’s shoulder and moved it back and forth.

“Mommy,” he said, “breakfast.”

She didn’t wake up.

He closed her legs and slid underneath so her feet rested on his lap. They were like spiders made of bones.

Mister Rogers was on. Mister Rogers said it’s normal to be angry. He said when you’re angry you use your words. You tell an adult. The adult would help you.

Then Mister Rogers started his little train and went to the kingdom where Lady Everly was.

The little king came out and was upset about something, but you could tell that the King’s voice was really Mister Rogers’ voice. So, really, you couldn’t believe anything anybody said.

Jimmy watched Guiding Light, Oprah, One Life to Live, General Hospital, Wheel of Fortune and the six o’clock news. Then Dick came over and gave his mother something to smell and she woke up and brushed off her arms and said, “Fucking pigeons.”

Dick laughed. He said, “We got, like, one hour.”

They got up and started picking up the house. They put the medicine in the medicine drawer. His mother was on her knees, hiding things.

“I vacuumed,” Jimmy said, “I vacuumed the whole apartment.”

His mother looked at him. She looked around the room. She looked at the floor.

“You’re the best boy in the whole world,” she said.

She put out her arms and he walked into them. He smelled the warm of her sleep still in the pool of collarbone under her sweater. He wanted to stay right there forever and ever. But the smell went away, and his mother was in a hurry.

“Okay, honey,” she said. She patted him on the back, which meant move away.

“We have to get ready for the doctor,” she said.

Something growled and clattered in the kitchen.

“Goddamn garbage disposal,” Dick yelled.

* * *

The sky looked like an animal the dog had shaken apart when Dr. Ming came. He wore a soft grey suit and a stiff white shirt and the most beautiful iridescent tie. Whenever he moved the tie changed colors.

“How’s our little man?” he said.

He put out his hand and Jimmy shook it. The hand was warm and soft and smelled like the baby powder his teacher used on her eczema.

Dr. Ming wore a patch over one eye and Jimmy said, “What’s behind the patch?”

And Dick said, “Where’s your manners?”

And Mom said, “Jimmy!”

But Dr. Ming said that’s okay. Then he turned to Jimmy.

“A little baby squirrel lives in there,” he said, “want to see?”

“No thank you,” Jimmy said. Although he kind of did.

Dr. Ming asked Jimmy to lie on the sofa. He pressed softly here and there on his belly. Mostly it seemed he just wanted to talk.

“Did your mother explain what was happening?” he asked.

“Just she wants to eat me,” Jimmy said.

“Not wants,” his mother said, “not wants.”

“But I want her to so she can live and be happy,” Jimmy said.

Dr. Ming’s eyes filled up with tears and he turned away.

“Oh, God,” his mother said.

“This,” Dr. Ming said, “is a very special child.”

He said it in a way that made Jimmy feel very warm and proud and heroic.

Then Dr. Ming got a very serious face and turned and looked at Jimmy for a long time.

“We think what happened,” he said, “is in the gestation process, when you were up there in your mother, what happened is, we think her heart got switched with yours.”

Dr. Ming looked so serious.

“Oh, I see,” Jimmy said.

“If somebody had something of yours, you’d want it back, wouldn’t you?”

“I know,” Jimmy said, “when Tim took my pocketknife and wouldn’t give it back.”

“It was a toy pocketknife,” his mother said.

“But you didn’t like that, did you?” Dr. Ming said.

“No.”

But actually, Jimmy didn’t mind because when Tim took it Tim looked happy because his mother hated knives and here was a knife in Tim’s hands and he was smiling.

“So now you know how your mother feels,” Dr. Ming said.

“I sure do,” Jimmy said.

“What an incredible child,” Dr. Ming said.

“Yeah, isn’t he great,” his mother said.

“He’s a freakin’ genius,” Dick said.

Dr. Ming looked at Dick for a moment. Dick looked back and knotted up his face to look like a smile.

“Well, then,” Dr. Ming said, “the day after tomorrow.”

“Should we get anything,” Dick said, “like some kinda barbeque sauce or something?”

Dr. Ming stood up and went over to Dick and looked him hard in the face.

“If you ever need a vasectomy,” he said to Dick, “I’d be happy to do yours for free.”

“Much obliged, Doctor,” Dick said.

When Dr. Ming left Dick lit a cigarette and took out the medicine and poured drinks.

“I liked that Dr. Waggle guy better,” Dick said.

“What?” his mother said. She’d been asleep.

“Is it because I wet my bed?” Jimmy asked.

“Is what,” his mother said.

“You want to eat me.”

“Kids these days,” Dick said, “where they come up with these ideas.”

“All kids wet their bed,” Mom said.

“Can I go to school tomorrow?” Jimmy asked.

“What for,” Dick said.

“If he wants to go to school let him go to school,” his mother said.

“Well yes ma’am Miss Queeny,” Dick said.

Then she held out her arm for the medicine.

Jimmy went into the kitchen and made macaroni and cheese.

* * *

At school the next day people looked at him funny. The teacher had runny eyes. After lunch Father McQuire invited Jimmy into his office and made him a big mug of hot chocolate.

He looked out the window and started talking.

“In the old days,” he said, “people just died.”

Bruce and Elsa walked by the open door and looked at him. Then a teacher made them move on. Father McQuire got up and closed the door.

“May I have another marshmallow?” Jimmy asked.

“Of course.”

Father McQuire dropped it into the mug. It bobbed in the chocolate. Jimmy liked to pinch the dry skin of the marshmallow and lift it out of the chocolate and suck the wet, sweet, chocolatey underside and then put it back in.

* * *

Father McQuire put his hand on Jimmy’s shoulder and said it was a damn shame this whole thing had been discovered. The church wasn’t for it but what could it do? The church was like a big spider web on earth and most people just walked through it. As soon as the whole thing started, the Vatican said, Okay, then, divorce. For Pete’s sake, divorce. But that didn’t satisfy anyone anymore.”

He reached in his drawer and removed a plate of cookies.

“Have some,” he said.

“Then it was these kids just didn’t show up at school and the police were. But. But now it’s so goddamn normal. Pardon my language. I don’t know. My point is I got this idea. Something like the underground railroad. You know what the underground railroad is?”

“The subway?” Jimmy’s mouth was full of dry, brittle chocolate chip cookies.

“No, like in the slave days. It’s just an idea but I’m working on it. For kids like you.”

Father McQuire looked at him and smiled.

“You take as many of those home as you want.”

* * *

Sometimes, when the bus went through the downtown there would be a man or a woman or a couple of people with those giant, red, glowing faces. Jimmy wondered if they had eaten their kids, too. He wondered what it must be like to be so happy your face looked like it would explode.

When he got home his mother was looking through a photo album of him as a baby.

“How was school?”

“I got hot chocolate in Father McQuire’s room.”

“Dick is bringing us Happy Meals from McDonald’s,” she said.

“Did he tell them to give us the boy toys?”

“I’m sure he did.”

“Last time I got that pink pony.”

“I’m sure you’ll get the boy’s one this time.”

“D’you think I can get home schooled,” Jimmy said.

“Oh, honey,” his mother said. She looked like she was going to cry. Her hair was combed back and dyed blue. It looked like feathers.

“I like your hair,” Jimmy said.

His mother turned her head and looked happy. She stroked the feathers.

“Thank you, I do, too,” she said.

“Will you read me a story tonight,” Jimmy said.

“Of course I will.”

* * *

That night she sat on his bed, and they ate potato chips and the onion dip she loved. She explained that everybody needs some happiness. She said she’d let Jimmy go around with her heart for eight years of happiness and there were children in Africa that only lived three years and the whole-time flies were eating their eyes out.

What do my eyes taste like, Jimmy said.

Maybe like blueberry jam, his mother said. And she said eight years is a long time for any one person to be happy when others couldn’t be.

“I’m sorry,” Jimmy said.

“Oh, honey, no, no, no,” she said, “that’s not what I meant. It’s just, you know, that’s all. You know what I mean.”

“Yes,” Jimmy said. But he had no idea what she meant.

Then she read the story about the bear that ate the ugly duckling then waddled out in the woods and pooped out a beautiful swan.

That always made him laugh but not tonight.

When she got up to go, he grabbed her hand. It had gotten so cold and scaly.

“Mom,” he said, “is it because I didn’t clean under my bed that time?”

“When?”

“I was supposed to, and I didn’t?”

“I don’t remember that stuff.”

Dick opened the door.

“I got the potatoes cut,” he said.

“Goodnight, sweetheart,” his mother said. She kissed him and the door closed.

* * *

He lay in the dark and listened to his heart thump. Each thump reminded him of something he’d done wrong.

The moon peeked in the corner of the room to see if he was eaten yet.

Jimmy got up, pulled all the sheets off his bed. On the mattress was the brown stain where he’d peed the bed so many times when he was three.

He got the beach pail from the back of his closet. He peeked out the door. The hall was dark. He could hear his mother and Dick in the kitchen. Dick had the hiccups. Each time he hiccupped he made a squeak and his mother laughed.

Jimmy slipped across the hall to the bathroom, filled the pail from the softly murmuring toilet, peeled the bar of soap off the bottom of the tub, poured bleach into the water from the jug under the sink then went back to his room.

He scrubbed the dark spot until sweat began to crawl out from under his hair and the lather rose up a yellow-brown. Then he poured water on the lather and soaked it up with a towel. When he was done, most of the spot was bleached white.

Then he opened the bedroom door and said, “Mom.”

“Oh, my god, now what?” Dick said.

His mother came in, looked at his bed.

“It’s all better,” Jimmy said.

His mother’s eyes looked like she’d had her medicine.

Dick stood in the doorway. He was chewing a big lump of something in his cheek.

“I told you to pee before you went to bed,” his mother said.

“Listen,” Dick said, “I can’t wait all night.”

“Go to bed,” his mother said.

“I’m a fuckin’ businessman,” Dick said.

“Just lay on the side,” his mother said.

“You want me to give him the pill,” Dick said.

“Just a minute,” she said.

She spread towels over the spot and left.

* * *

He lay on the towels and felt his heart thump. The small boats on his blanket bobbed about on the sea.

When he woke up, someone was sitting on his bed. A man.

“Dad?”

“No,” the man said, “Jesus. You know who Jesus is?”

“Oh. Yes. Jesus H. Christ,” Jimmy said.

“Good ol’ Dick,” Jesus said.

The moon had come all the way into Jimmy’s room. But it was caught in the trap of the mirror and maybe now it couldn’t get out. Everything in the room was glowing silver blue.

“Anyway,” Jesus said.

He took a nail file out of his robe. When he filed at his nails it sounded like the music his teacher used to play. Quiet and sad. But the kind of sad that makes you happy.

“Aren’t you supposed to be God,” Jimmy said.

“Yes and no,” Jesus said. “Anyway,” he said, “I’m sick to death about this. Everybody thinks it’s their God-given right to be happy but show me where it says that.”

“I just want my mom to be happy.”

Jesus shook his head. Shadows moved around the room when he did.

“You know what started this whole thing?”

“What?”

“Southwest Airlines offered twenty-five dollar tickets to Las Vegas.”

“Oh,” Jimmy said.

Jesus looked at him and smiled.

“It’s complicated,” he said, “but that was the beginning.”

“Am I really gonna get eaten?”

Jesus looked down at his hands. Some animal had chewed big holes in them.

“Eight years is too long for someone to have all the happiness,” Jimmy said.

Dick came in the room, looked. His shadow made a big clot of black air on the chair.

“Oh,” Dick said, “it’s you.”

Then he went out.

“It’s like this,” Jesus said, “like musical chairs. People think happiness is like all these chairs but there’s not gonna be one for them. They think someone else is gonna get their chair. It’s hard to explain. It’s like, there was this girl who was a groupie. You know what a groupie is? For a band?”

“I guess,” Jimmy said.

“She thought if she could sleep with every member of all the big bands, she’d collect all their talent. But you know what she got, don’t you?”

“What?”

“Let me put it this way. It wasn’t pretty.”

Jesus got up, looked in the mirror. He pulled the bottom of his eyes down and looked at the folds of wet, pink skin.

“But you know what,” Jesus said, “she was just a little girl who wanted to be loved.”

The moon hadn’t moved much but you could tell it was trying to get out of the mirror.

Then Jesus came back to the bed and sat down. He took Jimmy’s hand in his. Even with the holes it didn’t feel weird. It felt warm and kind and gentle. It felt like the best story his mother ever read to him except it was in his hands and not in his head.

Then he looked at Jesus’ face and his face was all twisted up and there were tears coming out of his eyes.

“What’s wrong,” Jimmy said.

“It’s just,” Jesus said, “you do this a billion times, and it never gets any easier.”

“What doesn’t?”

“Oh, nothing,” Jesus said. He wiped his nose on his sleeve and snuffed everything up and smiled a wet smile.

Then he said, “Hey, I brought something really cool, okay?”

“Okay,” Jimmy said.

Jesus took out a little key, like the key they used to use to wind-up old-fashioned toys that chattered and banged about the floor.

“Take off your shirt, okay?”

Jimmy took off his shirt. He felt Jesus’ warm fingertips touch the little bones that stuck out in his back. Then he felt something warm go into his side.

“Okay,” Jesus said.

Then he put his hands under Jimmy’s armpits and lifted him up on the windowsill. He opened the window and all the stars crowded down around the house to see.

“Now, lift up your arms,” he said.

Jimmy lifted his arms and started to float, out the window and up.

“Wow,” he said, “wow.”

After awhile he floated back down to his room.

When he climbed in the window the moon was gone and the room was torn to shreds, the way a wolf tears open a rabbit hole but can’t find the rabbit and leaves. There were big blotches of blood everywhere.

Jimmy set the chair back on its feet and sat down. The moon glared at him from the bushes.

In a few minutes the door opened. His mother leaned in. She was smiling.

“Come look,” she said.

In the dining room candles were lit and there was a big, cooked fish on the table with vegetables and a big round loaf of bread and glasses of wine.

“I just came in,” his mom said, “and here it was.”

Jimmy and his mother and Dick sat down and started to eat. They were so hungry.

Nobody said anything it was so good.

All through the meal Dick scratched at his tattoo with his fork until it turned into a red mess.

“Can I taste the wine?” Jimmy said.

“Of course,” his mother said.

It tasted bitter and good, and it melted in his mouth.

After awhile Dick got up and went to the bathroom and started to vomit. But Jimmy’s mother sat back in her chair and smiled at Jimmy. Her face was full and warm. Her eyes sparkled.

“Oh, my God,” she said, “oh, my God.”

She put her hands on her big, warm belly.

Jimmy said, “You want some more?”

But his mother shook her head and smiled.

“No, honey” she said, “I couldn’t. I’m so full.”

Payne holds an MFA in fiction from Stonecoast. He writes fiction and plays. His short story “Fish Story” won The New Guard’s Machigonne Fiction Contest. His story, “Fullness” was a finalist in the Fractured Lit flash fiction contest. Several of his plays have won awards and been produced in Boston, San Francisco, New York, and Maine. One ten-minute play is published by Samuel French. He makes a living writing radio commercials which are broadcast nationally. He has acted in multiple theaters and productions in Maine and Kansas.

Payne holds an MFA in fiction from Stonecoast. He writes fiction and plays. His short story “Fish Story” won The New Guard’s Machigonne Fiction Contest. His story, “Fullness” was a finalist in the Fractured Lit flash fiction contest. Several of his plays have won awards and been produced in Boston, San Francisco, New York, and Maine. One ten-minute play is published by Samuel French. He makes a living writing radio commercials which are broadcast nationally. He has acted in multiple theaters and productions in Maine and Kansas.