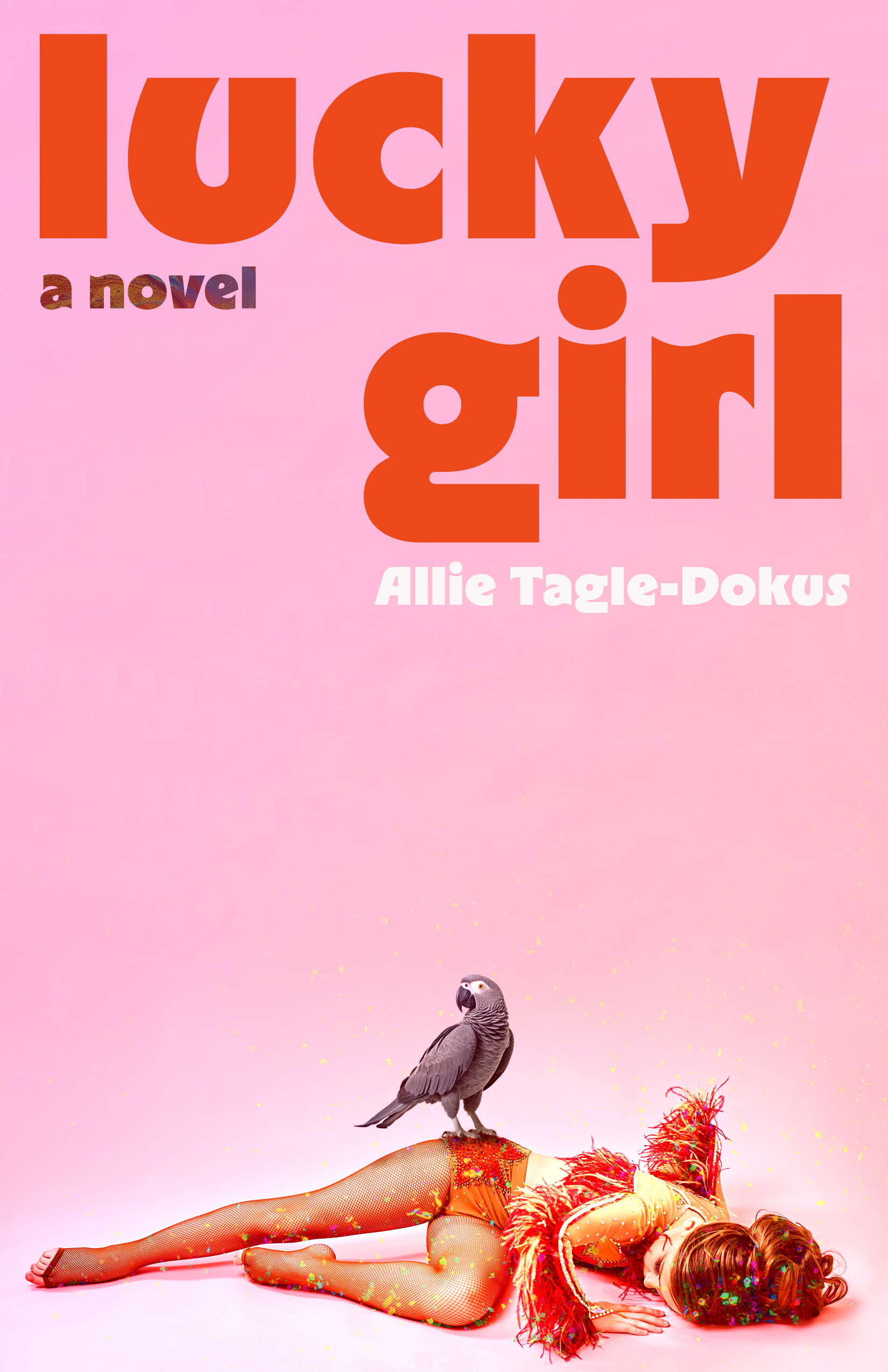

To tell you that Lucky Girl, Allie Tagle-Dokus’s debut novel, is about the rise from child stardom to life-ruining fame gives you a sense of the pleasures of this novel, but not the joys.

To tell you that Lucky Girl, Allie Tagle-Dokus’s debut novel, is about the rise from child stardom to life-ruining fame gives you a sense of the pleasures of this novel, but not the joys.

Lucy Gardiner, protagonist, is an eleven-year-old dancer, rising through the ranks of junior competitions. Her mother, the financial and logistical bedrock of a disintegrating family, supports Lucy’s burgeoning career at the expense of the family unit. When Lucy is cast on a reality TV dance competition, she gets her big break: A legendary popstar discovers her and whisks her away to star in a viral music video. Lucy performs in subsequent music videos, and then concert tours, movies, and TV shows, sacrificing friends and passion as her career approaches its apex. And then everything plummets.

This is not a spoiler, because Lucy Gardiner, narrator, warns us early of “how twisted and ruined my life would become.” Lucy’s steps toward fame are dogged by tradeoffs; the chapters of Part I are titled after the people she loses to estrangement, from a childhood best friend to a dance partner to a family member. A collapse is coming, made inevitable not only by the retrospective narration but by the nature of dance itself: “You weren’t a dancer for very long. Your body is a bag of sand with a hole.” This understanding propels Lucy’s single-minded ambition: every chance is a chance she must take.

Lucy narrates the story of her rise and fall from a distance that is not as great as the reader initially believes. She knows what happened to her, but she is still sorting through what it means. She tries, as much as possible, to let events stand for themselves, but can’t help editorializing her worst moments, torn between the desire to justify herself and the desire to condemn herself. “These are excuses. I was eleven,” she says, and later, at twelve: “It’s not an excuse… I was just trying to make sense of what I was seeing. This is not an excuse.”

As the years pass, the balance tips toward condemnation. By sixteen, Lucy is, in her own telling, “a failure who disappoints everyone,” “an awful friend and an awful person.” Her self-evaluation is helplessly tied to how she is perceived: “I read everything online fervently, waiting to see how much I should hate myself.”

What drives the plot forward is Lucy’s pursuit of fame, but what drives the narration is an equally compelling search for some objective allotment of guilt: When exactly was she old enough to know better? That is the real ticking clock of this novel, as if, at the stroke of midnight, Lucy transforms from victim into villain. But she can never settle on exactly when midnight occurred: “She was so young. It wasn’t not her fault. But still… Would I forgive her, if she wasn’t me?”

Lucy is thrown into fame at eleven years old, and ends the novel not much older. Many of her decisions are the decision to go along with things, to keep quiet, to hope for the best, to do what she’s told. This is not to say she is a passive character—in fact, one the most striking aspects of the novel is its excoriation of passivity. The plot turns on moments of crucial inaction, not action, and Lucy the narrator insists upon these moments as choices, telling us what she could have done differently, what she wishes she had done, what would have been just as easy and natural for her to do. Her failure to act instigates the action; the plot proves that to avoid something until a decision is made for you is, in fact, to make a decision.

We see this clearly in the novel’s opening chapter. Lucy’s best friend Kimberly has been planning her own eleventh birthday party for months. It will be just the two of them; Kimberly is unpopular, and Lucy is her only close friend. But on the same day as Kimberly’s birthday is a dance competition, which Lucy needs to win in order to qualify for a more important dance competition.

Lucy can’t face the thought of disappointing Kimberly: “I didn’t want to hurt her, so I put it off. And then time passed. And then it was too late.” But of course, it never was too late. Up to the last minute, Lucy pretends she’s coming to Kimberly’s party: “I simply allowed myself to believe both were possible until I was sitting in the Logan terminal at four in the morning…”

Lucy flies to the dance competition—and the page splits into two columns, tracking each minute as Lucy ascends the stage and Kimberly sits alone at the Melting Pot, stood up for her own birthday party. The scene is devastating, nightmarishly relatable, and unflinching in its insistence that passivity masks constant, purposeful action.

The two-column sections are the most distinctive stylistic trick of Lucky Girl, and they play out to varying degrees of success. One of the longer chapters in the book portrays Lucy’s tenure on a reality TV show, split into three segments: a left-side column narrating the episodes, a right-side column of confessionals, and underneath both columns, a full-width section that captures what actually happened. Reality TV is the perfect candidate for this kind of fractured narration, but the staging isn’t quite right. A more resonant layout would have pitted what Lucy remembers directly against what the camera remembers—after all, the gap between the two will haunt Lucy throughout the rest of the novel.

The flashy formatting is the novel’s most obvious break from convention, but there are subtler surprises at work. One such surprise is the depiction of the popstar Bruise, who, in the hands of any other writer, would be magnetic, dangerously charismatic, and obsessed with Lucy in a way that veered sexual. But Bruise is not that kind of threat; she is, as Lucy realizes with dawning horror, just a shallow, “boring” person, “incapable of sustaining deep, evolving relationships.” Bruise has no evil agenda—she’s simply washed-up, and clutching at straws. This is somehow more disquieting than the grooming narrative that the reader expects. The most damaging people, the novel suggests, are the ones who cannot grow.

The foils to Bruise are Lucy’s mother and brother, who absolutely steal the show with their setbacks and recoveries. Lucy’s relationship with her family is the enduring heart of the book; everything else—the fame and the ambition and the scandal—feels slippery in comparison, and intentionally so. Tagle-Dokus has created a character who misses what’s important most of the time, but it’s all there for the reader to witness and to learn from, a cautionary tale that calls out ambition without gratitude, acquiescence without accountability.

Lucky Girl, already destined by its premise to be a fun book, outperforms on every metric: It is sharp, wise, heartfelt, daring, and memorable. It swings so often that I could hardly begrudge the misses. I wish more novels took the imaginative chances that this novel takes; I would rather watch an interesting writer fail than a boring writer succeed, and fortunately, Tagle-Dokus mostly succeeds in her undeniably interesting debut.

Publisher: Tin House Books

Publication Date: November 11, 2025

Reviewed by Devon Halliday