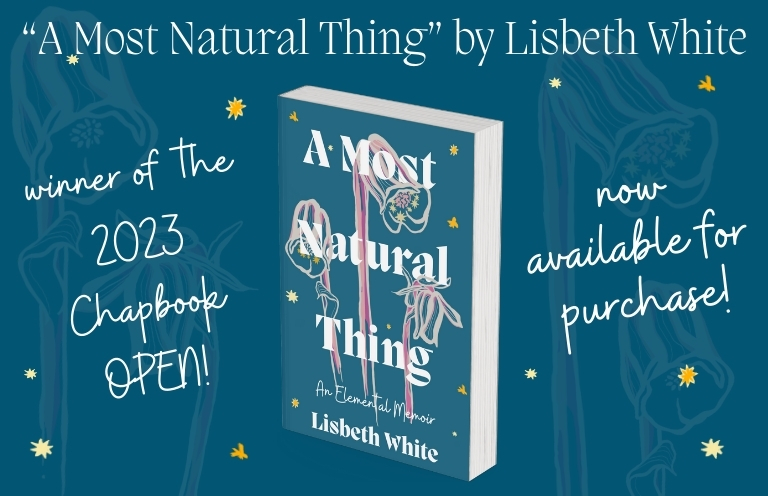

Lisbeth White’s lyrical and formally inventive chapbook, selected by Michael Martone as the winner of our 2023 Chapbook Open, is now available for purchase through Red Mare Press! Part travel-writing, part ecopoetical mythology, part memoir of healing, A Most Natural Thing: An Elemental Memoir is alive with longing as it explores our connection with, and duty to, not just each other, but all the natural world. Read Michael Martone’s introduction to this terrific new memoir and then pick up a copy of your own!

Natural Unnaturalness

If a painter in the nineteenth century could render a mimetic, realistic, three-dimensional picture of a horse, say, on a flat canvas, we would agree even if wasn’t art that not everyone could do it. It required skill and training and study and a certain gift, an “eye.” The twentieth century arrives along with the cheap Brownie camera and overnight anyone, it seems, can make a picture of a horse. In response, painters, both artists and amateurs, had to face, in the face of such competition, an existential question. What is it that paint can do that a photograph cannot? And they answered with abstraction. Paint as paint. Color for color’s sake. Not the illusion of depth but the use of flat-out flat for flat’s sake flatness. They answered the challenge by painting what only paint could do.

The same might be said about the nineteenth century narrative writer who took to the field with prose—fiction or nonfiction. What was the competition? Newspapers maybe, another form of narrative delivery device like the novel, like the short story, like the essay. But those forms were printed in newspapers anyway. The twentieth century brings a whole slew of new narrative delivery devices: movies, radio, television, streaming, cable, podcasts, AA Meetings. Book writers, writers using print, could respond as the painters did. What is it the book can do, what can print do, that all these other delivery devices cannot do?

A Most Natural Thing: An Elemental Memoir by Lisbeth White is one fine response, a founding example and confounding answer to the question of what only a book can do.

You can’t imagine this chapbook as anything other than what it is. What movie could be made of it? It is certainly visual in its making visible the usually invisible conventions and defaults of printing and punctuation. Three columns instead of one! Crots! Dingbats! White spaces! Bullet points! The visual virtuosity here is unique to print and to the defamiliarization of the conventional printed spaces we most often inhabit. And how do you make a podcast or radio report of this this? You can’t. You can’t “follow” it with the ear. It isn’t linear. In that sense it doesn’t have a “voice.” It modulates. It yawns. It barks. There are beautiful types of silences between the buzz of the types of type. It isn’t a script. It doesn’t have a beginning, middle, or even an end.

You might think of White’s memoir more like a map, remembering that like all maps it unfolds and folds. It spreads and bleeds. It is distorted to emphasize and exaggerate. Borges expands that notion, captures the ambitious attempt here when he asks us to imagine a map that is more detailed than the thing it represents. Keep that in mind.

Writers realize that they cannot be abstract in the way that painters can be. I can write CAT and you, reader, will think of the four-legged feline, a tracked vehicle, a kind of scan, a house of ill repute. You will not think this: What a lovely sheen in the ink. I like the kern in the spacing. See how the serifs hang and sway. To go abstract Lisbeth White exposes expertly the received gestures found in the acts (already abstract and abstracting) of writing and reading and invites the reader to participate (in new and different ways) in the creation of meaning.

The existential nature of this art form is linear. We read, in English, left to right, word after word, from the top of the page to the bottom. The story wants to line up. Narrative wants to “flow.” But A Most Natural Thing is unnatural in its great way, and White is adept at the disturbing disruptions on the page, forcing the eye to act differently, to read this narrative the way one “reads” a painting, to see everything all at once. Here is a text that is, yes, elemental. Like fire, earth, water, and air. We are immersed, consumed, engulfed, drowned. Like carbon, A Most Natural Thing has four hands. And it places the reader in a printed quantum realm of asymmetrical simultaneity made up of various matrices, lattices, solid and dissolving geometries of texts, sublime and sublimated tetrahedral chains that are fertile, organic, fractured, original.

—Michael Martone, guest judge