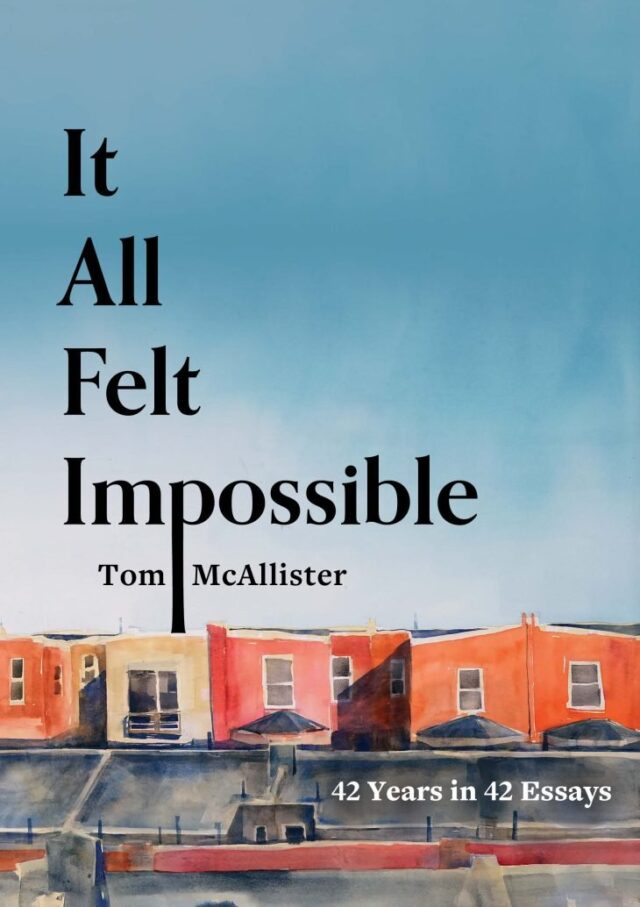

What does it really mean to examine your life—one year at a time? In It All Felt Impossible: 42 Years in 42 Essays, from Rose Metal Press, Tom McAllister takes on a writing challenge with humor, honesty, and a sharp eye for the little details that build a life. By condensing each year into a short, insightful essay, he’s not just telling his own story—he’s capturing what it felt like to grow up, stumble into adulthood, and navigate the chaos of modern America. Born during the Reagan years and influenced by television, social media, and the defining products of the era, his essays trace how these cultural forces influenced a generation’s coming-of-age. With sharp observation and a cool sensibility reminiscent of Chuck Klosterman and Sloan Crosley, McAllister’s collection is both perceptive and entertaining, offering a deeply relatable reflection on life and an honest, thoughtful exploration of what it means to be human.

What does it really mean to examine your life—one year at a time? In It All Felt Impossible: 42 Years in 42 Essays, from Rose Metal Press, Tom McAllister takes on a writing challenge with humor, honesty, and a sharp eye for the little details that build a life. By condensing each year into a short, insightful essay, he’s not just telling his own story—he’s capturing what it felt like to grow up, stumble into adulthood, and navigate the chaos of modern America. Born during the Reagan years and influenced by television, social media, and the defining products of the era, his essays trace how these cultural forces influenced a generation’s coming-of-age. With sharp observation and a cool sensibility reminiscent of Chuck Klosterman and Sloan Crosley, McAllister’s collection is both perceptive and entertaining, offering a deeply relatable reflection on life and an honest, thoughtful exploration of what it means to be human.

With the wisdom of experience, an adult McAllister reflects on the common realities of being raised in 1980s suburban America, particularly examining the roles that adults and media play in shaping a child’s development. He writes:

Like most American families, our living space was structured around the TV, so even if I wasn’t watching myself, I knew its presence, found comfort in the static as my parents fiddled with the antenna, tracked the wild colors bounding across the screen, felt the fine hairs on my arm standing up and reaching toward it. I was already being shaped by TV.

Comedically, this worship of media penetrates organized religion, as McAllister sits in church on Sunday with his family and prays to be transported into his favorite sitcoms. This media obsession extends beyond the screen, influencing even his childhood toys. He reflects on how his early birthday presents evolved from building blocks to weapons and G.I. Joes in a short time, and that it was “normal to play by pretending to kill people over and over again.” This awareness of media’s impact on us highlights the indoctrination aspect of American culture, where entertainment becomes a tool for shaping societal values and perceptions of gender, with McAllister highlighting how “the concept of masculinity is poisoned from birth.” Like the wholesome boy in The Emperor’s New Clothes, McAllister does not provide solutions but is unable to ignore the undeniable and uncomfortable truths of culture’s impact on our childhoods—powerful forces that shape our worldview as adults.

Having survived the wrath of online chatroom feuds and the relentless grip of the mushroom haircut trend that swept through American middle schools in the early 1990s, McAllister adaptively navigates his place at school and within his family. Through high school, this malleability serves him well, though it also makes him susceptible to the standard peer pressure, fighting, and the ruthless competition for popularity. Later, his college years reveal a stark contrast between his better judgment and the temptation of hedonistic distractions. Like any young adult being unleashed into college life, McAllister eloquently justifies his life choices stating that “everyone was drunk and determined to have an experience that felt meaningful.” Readers will relate to the confusing years leading up to real adulthood, a time when many find themselves either trapped by their choices or on the verge of being so. McAllister’s writing offers a candid reflection on these familiar complexities, particularly when the desire for stability looms just ahead. He states, “Sleeping on the floor of a dingy Ocean City condo, beer bottles scattered everywhere, the sound of an endless game of beer pong clattering in the background, I was seven months from meeting the woman I would eventually marry.” Readers sense the change—after meeting his future wife, McAllister’s youthful selfishness and adolescent sense of invincibility quickly give way to a deepened empathy for others which becomes the driving force behind his success as an educator.

Time once spent playing video games and getting drunk is replaced with gender- reveal parties, weddings, and teaching at the college level. As readers witness a life evolving in poignant snapshots, it’s clear that McAllister cannot ignore the pattern that the cultural tide keeps pushing ashore—systemic racism, casual misogyny, political hypocrisy, and prideful ignorance—and he does his earnest best to combat against them through unwavering support and awareness. This growing empathy becomes vital in his newfound role in academia. Confronted with the newer generation—one that is seemingly screen-obsessed, disengaged, and apathetic—McAllister embraces a refreshing sense of responsibility. Instead of the usual teacher-burnout narrative, he insightfully claims: “The whole point is for me to help them navigate a stressful, challenging time in their lives and give them the tools to come out on the other side a little better prepared, a little more open-minded, a little more skilled.” Harkening back to his immature and insecure early years, McAllister recognizes that his position goes beyond simply imparting knowledge; it is about offering guidance through the complexities and pressures of existing within a culture saturated in misinformation and driven by dopamine-addiction. He becomes the teacher he needed himself—his perspective shows how important it is to encourage critical thinking and compassion. Being encouraged to complain about the newer generation, he declines, claiming that his students trust him “to help them improve their odds just a little bit.”

The passing years prove that time doesn’t heal everything, but, as McAllister notes, “if you live long enough, you can outrun almost anything.” His honesty is unflinching— sometimes the girl doesn’t kiss back, men make fools of themselves to impress their friends, and we all have one humiliating night of drinking we’d rather forget. His reflections capture the universal struggle to rise above our circumstances in a world increasingly fractured by divisiveness and ignorance. While these essays may not offer groundbreaking revelations about the human condition, they underscore a simple yet profound truth: The smallest details matter. Each passing year awakens him to moments worth savoring—above all, the humble experience of loving and being loved in return.

Reading McAllister’s self-aware, relaxed narration feels like swapping stories with an old friend by a bonfire as he effortlessly verbalizes unsaid truths about aging friendships and shifting family dynamics. Amusingly, he hopes that one day critics will describe his work as “penetrating,” “illuminating,” and “deeply felt,” and frankly, I agree; It All Felt Impossible delivers on all those fronts. Through these interconnected essays, readers witness a person striving to become their best self amid chaos—a boy growing into a man, a student evolving into a teacher, and a follower transforming into a leader—a humble journey shaped by time and quiet reflection.

Publisher: Rose Metal Press

Publication date: May 14, 2025

Reviewed by Mark Massaro

Mark Massaro earned a master’s degree in English Language & Literature from Florida Gulf Coast University. He is currently a Professor of English at a state college in Florida. His writing has been published in DASH, Litro, Newsweek, The Georgia Review, The Hill, Los Angeles Review of Books, Rain Taxi Review, The Sunlight Press, and others.