A deliciously rebellious take on the classic romance novel form, The Book of Love plunges into adored (and despised) tropes of the genre and guts them, often with humor, sometimes with gore, and always with, well, love—for as much as our protagonists’ future in the mortal world is entangled in the baffling affairs of immortals, that doesn’t stop them from dipping their toes in new relationships, revisiting old ones, or remembering what it’s like to be human and vulnerable. You never know when someone might be turned into a bear, or get to make out with a really hot boy (who’s actually been alive for over 300 years), or burst into a swarm of blue moths.

A deliciously rebellious take on the classic romance novel form, The Book of Love plunges into adored (and despised) tropes of the genre and guts them, often with humor, sometimes with gore, and always with, well, love—for as much as our protagonists’ future in the mortal world is entangled in the baffling affairs of immortals, that doesn’t stop them from dipping their toes in new relationships, revisiting old ones, or remembering what it’s like to be human and vulnerable. You never know when someone might be turned into a bear, or get to make out with a really hot boy (who’s actually been alive for over 300 years), or burst into a swarm of blue moths.

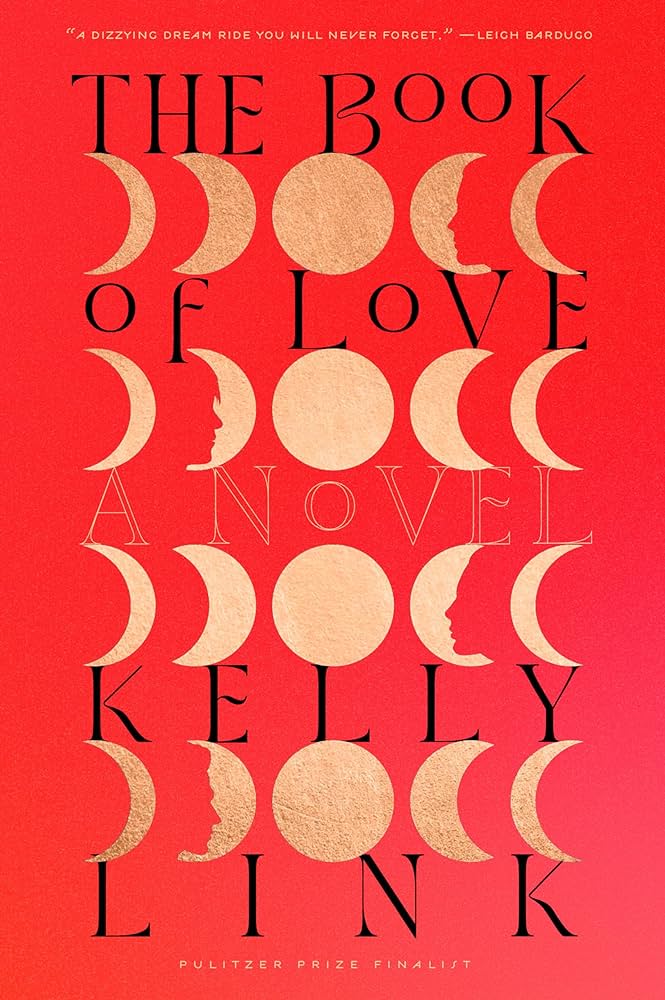

Bestselling author of fabulist short stories Kelly Link recently released her debut novel, which opens with three teenagers, and one outlier, who have found themselves in the music room of their high school wearing theatrical costumes, their bare feet filthy and bodies built anew, and with more questions than they’ll learn the answers to any time soon. What they do know is that they were dead, and now they’re not. Acting as equal-parts intrepid guides and intimidating puppet masters in this charade, their music teacher, Mr. Anabin, and Bogomil, taking the form of a scary dog, together devise a series of trials the four must succeed in if they want to stay in the realm of the living. But there’s a caveat, which Bogomil scrawls on the blackboard: two return, two remain.

There’s a bluntness with which Link cuts down these young characters already reckoning with their tenuous reality and the magic they now possess, both in the near-spooks woven into the fabric of the ordinary lives they return to—like touching a cold wet nose that turns out not to belong to the family dog—and the very real encounters with the supernatural, which, in believable teenage fashion are often faced with irreverence and snark. If a fate worse than the threat of returning to their untimely, uncanny deaths exists, the villains that descend on this imaginary seaside town of Lovesend, Massachusetts are eager to show them what that looks like.

Told in third-person perspectives alternating with each chapter, the obvious characters for the narrative to follow would be the four apparent pawns in this scheme—high school students Laura, Daniel, and Mo, and the fourth being, dubbed Bowie, who tumbled out of the purgatory realm without memory of who they once were—and a fifth, Susannah. The sister of Laura, on-again-off-again girlfriend of Daniel, and singer in the trio’s band, Susannah is banished to the periphery of the others’ trials, but a nagging splinter in her heel is poised to reveal her involvement in it all.

But these five are far from the only voices accumulated in the telling, with the scope broadening to encompass the entire town, and even as the old grudges and unbridled hunger of Lovesend’s more mysterious visitors and inhabitants are added to this stew of exquisite chaos, the pot, so to speak, never quite bubbles over into something unmanageable. The threads feel balanced, each compelling in their own right.

Many events unfold in a grandiose scale, in the trappings of absurdism and garish outfits. People transformed into animals, by their own will or another’s, are often in the midst of hot pursuit or escape. A beach bar with a carousel becomes the site of shady magical dealings, and being a teenage rockstar is akin to being god.

But it’s often the small moments—which, in a novel with so much big magic, could be overshadowed—that are the source of the most wrenching gut punches, and also joy. There’s traces of grief ungrieved under the surface of memories stitched together by Mr. Anabin to explain away the year the teenagers lost to being dead, and Daniel lovingly tidying the kitchen and putting sheets in the wash when he gets home from that first turbulent night of being alive again.

There’s also stagnation and indecision and the uncomfortable, murky feelings that come with growing up and being on the cusp of wanting and not knowing what to want, in equal measure. While Susannah is harped on by her family for working at a coffee shop post-graduation and not doing her laundry, Laura’s ambition is palpable, and, at times, satisfyingly annoying. In circumstances less ordinary, the magical thread of tension often forces these characters to act quickly, and at times gives them the freedom to opt out, to not choose, but not forever.

Presiding as a sort of matriarch over the novel, Mo’s grandmother Maryanne Gorch’s presence is felt in the town even after her death, not only in Mo’s profound grief for the woman who raised him, but also in the statues of Black figures of historical note she commissioned to be placed all over the predominantly white town. Her presence in The Book of Love is twofold—as a famous self-made romance novelist, her formula for love stories is also positioned against the character arcs that unfold in a lightly meta way, from terrible struggles to the promise of happy endings—no matter the twisted forms those plot devices may take.

Despite at times feeling like a wild romp through a universe where literally anything is possible with the right amount of will and magic, the reader is fed the mechanics of this world at a pace that, for the most part, does not overwhelm, and dangles enough of a sense of mystery in front of you to satiate until the end, which escalates into a thrilling whirlwind of magic and emotion. Patterns are ruptured and reinvented. Old myths make way for new ones.

This New England reader delighted in cracking open a ‘Gansett while snow did and sometimes didn’t fall outside the window, and over this fantastical world that at times felt so eerily real and close.

Publisher: Random House

Publication Date: February 13, 2024

Reviewed by Abbie Lahmers

Abbie Lahmers earned an MFA in fiction from Georgia College and State University and was formerly a managing editor of Arts & Letters. Her fiction has appeared in small-circulation journals, including Flyway: Journal of Writing and Environment, Barnstorm, Pif Magazine, and others. She currently lives in Providence, RI, writing and editing for local lifestyle magazines, camping around New England, and posting about plants and books on Instagram (@fauna.and.fronds).