In a world on the verge of extinction, small groups of human beings across the planet exist under the careful watch of “Mothers” and “watchers,” evolving unique societies, ways of living, and methods of reproducing. Some have developed the ability to nourish themselves through photosynthesis, gradually becoming more plant-like than human. Others produce children in factories using the cells of non-human animals. Others are cloned, growing up with multiple versions of themselves. Still, there are schools and relationships, love and heartbreak, envy, compassion, and the messiness of daily survival. At the end of human existence, the true nature of humanity is laid bare.

In a world on the verge of extinction, small groups of human beings across the planet exist under the careful watch of “Mothers” and “watchers,” evolving unique societies, ways of living, and methods of reproducing. Some have developed the ability to nourish themselves through photosynthesis, gradually becoming more plant-like than human. Others produce children in factories using the cells of non-human animals. Others are cloned, growing up with multiple versions of themselves. Still, there are schools and relationships, love and heartbreak, envy, compassion, and the messiness of daily survival. At the end of human existence, the true nature of humanity is laid bare.

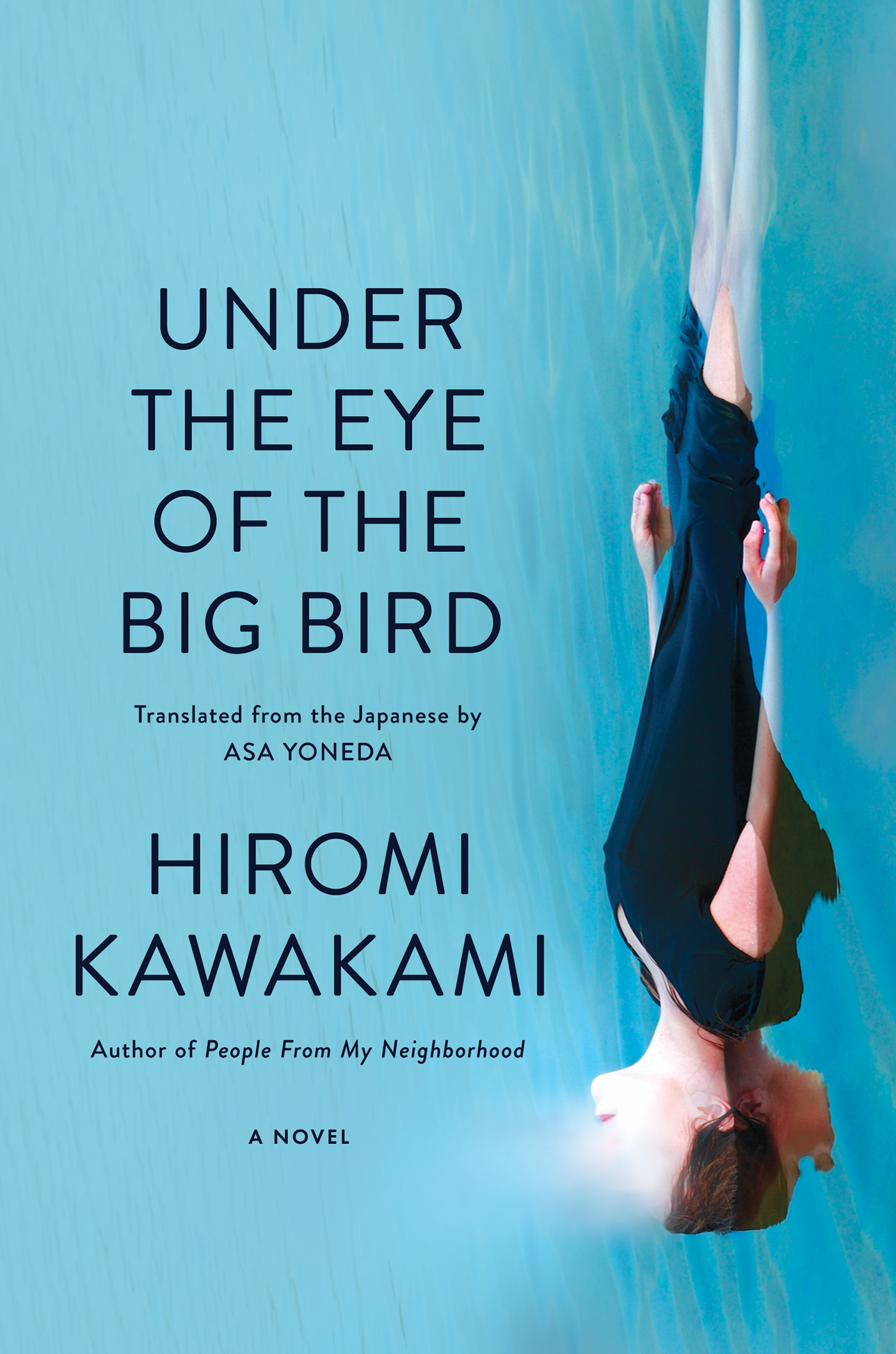

Hiromi Kawakami’s Under the Eye of the Big Bird, a novel in stories translated from Japanese by Asa Yoneda, is a masterpiece of speculative fiction. Few books hold attention the way this one does, resonating with both the present moment and fears of a perhaps not-too-distant future. It is an intimate, complex, and raw exploration of what it means to be human, of the strengths and weaknesses of the species, and what that means for our survival and our extinction. Joining the literary genius of authors like Richard Bach, Daniel Quinn, Paulo Coelho and Rebecca Solnit, Kawakami’s writing evokes a rare depth of contemplation and self-reflection. For readers approaching this novel with an open mind, these fourteen stories ranging across geological epochs and a diversity of communities will prompt a spectrum of emotions: grief at what we stand to lose, admiration for the resilience inherent in human beings, frustration at our irrationality, and a desire for connection and love when everything else is vanishing.

At once philosophical and mythological, Under the Eye of the Big Bird manages to create a startling and vivid world while filling the pages with profound realizations. Observing the decline of humankind, a watcher mourns, “We were supposed to be so much more than this”, but “[as] a species we were like an octopus trying to survive by eating its own limbs. And while we all saw the fatal error we were making, no one stepped forward with a decisive solution.” In another conversation between a Mother and a human named Kyla, the Mother tells Kyla that she is “…a very human human,” because “you create things, and you destroy more than you create.” Later, a Mother explains humanity’s inevitable demise: “You lack judgment. You do… The way you’re made makes it difficult for you to perceive your own positions from an objective standpoint.” Yet even when faced with extinction, “[t]he humans kept doing the same things: loving one another, hating one another, fighting one another…You’d think they might have come up with something else to try, but no matter how many times they went around, they couldn’t seem to change course… That was enough—humans couldn’t change.”

Readers who stay with the novel despite its moments of ambiguity will be rewarded with revelations at the end, tying the story together in ways that are mesmerizing in their grandeur and execution. While there are hints and suggestions along the way, it is in the ending that the true genius and foresight of Kawakami is revealed. One conversation in the final chapters strikes a particularly poignant chord:

“Did the humans keep loving and hating one another, even up to the end?”

“That’s right. They were constant; almost admirably so, all the way until the end.”

“Even as they went extinct, they were still loving and hating?”

“Yes, just like they used to before they ever started their decline—each one loving and hating right up to their last breath.”

Looking at the world today, it is not hard to imagine a future similar to the one portrayed in Under the Eye of the Big Bird. But what Kawakami does is give us the distance of speculative fiction to see beneath the surface of our own disillusions: how power corrupts, how envy destroys, how love and connection persevere. She offers us a chance to consider a different course than the one we are currently on. At the same time, there is an unabashed, almost mournful, acknowledgement of our historical inability to change, and of the fallibility of being human: “Humans make no sense.”

Under the Eye of the Big Bird is a novel to return to again and again, one that reveals deeper layers of meaning with each passing. It is a book to be kept on bedside tables as a reminder of the choices we have the power to make, and the consequences of what we decide. It is a warning, a prophecy, and, maybe—if we choose it to be, if we choose to change—a chance to hope for a different ending.

Publisher: Soft Skull Press

Publication date: September 3rd, 2024

Reviewed by Justine Payton

Justine Payton is an MFA candidate at the University of North Carolina-Wilmington where she is a recipient of the Philip Gerard Graduate Fellowship and the Bernice Kert Fellowship in Creative Writing. She has been published or has work forthcoming in the Bellevue Literary Review, Isele Magazine, The Masters Review, The Keeping Room, and others. She is currently the managing editor of ONLY POEMS and an editor for Ecotone Magazine.