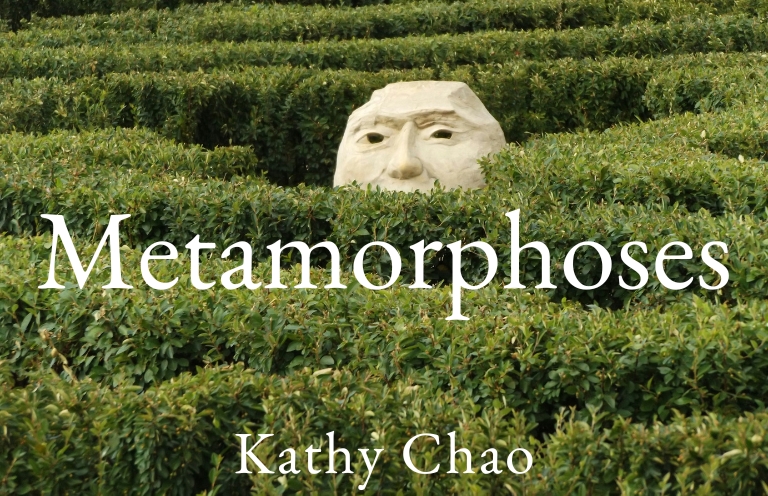

Part excavation of grief, part magical realism, Kathy Chao’s “Metamorphoses” is a story about the power of language. To assimilate, the narrator’s father learns words from the dictionary and makes her do the same. When dementia comes for him, those words become her lifeline.

As soon as I heard, on the night of the memorial service, my father’s voice drifting in on a breeze of honeysuckle—“Aloe, alogical, aloha, alone”—I knew that he was not gone, not vanished, not dead at all. He was only in the garden, trapped in the maze.

“Ba!” I leapt from his cracked recliner, where I’d been nodding and dozing and inhaling the mothball scent of his old age.

“Ba!”

Racing into the night, coat undone, hair streaming like a Japanese poltergeist. Into the half-light of the full moon, the late spring chill, the labyrinth grown monstrous, twice my height, since its mad architect disappeared off the face of the earth.

* * *

Look to Ba, half a century earlier—twenty-one, clear-eyed, resolute.

Landscape architect, he announced himself. And why not? He was freshly degreed, top of his village class. In the squat tropics of his island home he dreamed of English gardens—trellised wisteria, stone manors with orangeries, ivy cloaking entire south walls. And always, mazes. Mazes of yew and laurel and boxwood and holly. Mazes clenched like conches, unfurling.

Look at him, nose twitching with ambition. Absconding from the impoverished homeland with nothing but a knapsack and a tourist visa he was determined to overstay. Imagining himself a young Daedalus, striking out.

Imagine his disappointment on finding himself, in this new world, just another minotaur.

* * *

“Ba?”

“Here, hereby, hereditary.”

“I can’t—”

I ran into a whipping branch, headlong into something sticky with sap. Two minutes into this infernal maze and already I was lost.

The feeble voice: “M…m…”

“What?” No wonder I avoided this place like the plague.

“Member…”

No wonder I never visited. No wonder—

“Membrane… Memoir…”

Memory.

I stopped my thrashing. Of course. The memory trick.

* * *

Long ago, a moonless night. Ba’s face ghouled by the underlight of the lantern.

“Associations,” he said, his breath foul with alliums.

Each step a beat, each turn a word. Alphabetical.

He waited until I could recite them all, forward and back, then smiled a smile made terrible by torchlight.

“Now,” he said, “labyrinth in your head. Now you can walk in day, in night”—the beam flickered out, plunging us into darkness—“even with no eyes.”

“Now,” he said. “Begin.”

* * *

I took a deep, piney breath. Shut my eyes. Began.

“Apple, arabesque, arachnid.”

Turning by memory, gliding through corridors that opened to me like gates.

From deep within the hedges, Ba’s voice my echo: “Abscond, absent, accent.”

* * *

The same chants he once recited as he huffed lawnmowers across over-manicured estates, clipped hemlock into unnatural forms of man and beast.

“Dictionary,” he bragged over the oil-clothed dinner table. “I learn all.”

English to him a jumble of loose wires, waiting to be wrenched into the shape of his poetry.

He rubbed his sun-chapped cheek and honked through the wobbly new sounds:

“Moody, moolah, moon. Moon-eyed. Moon-faced.”

From a distance you could mistake it for the lowing of a bull-headed beast. A minotaur enumerating its mistakes. Where it’d taken a false turn, where it’d doubled back. How far it’d wandered from a calfhood of light and air.

* * *

Closer. I could sense his movements. Fidgety. Birdlike.

* * *

In the long years of his decline, before his exile to the Home, Ba rediscovered the labyrinth that had sat untended since I breezed away at a scornful eighteen.

Again with the pruning, the trimming, the tender shaping of its trickster walls. He could lose himself in the work. First all morning, then all day, then half the wind-swept night.

One rare visit I sat up until dawn, the tea long cooled, until he came slinking in, palms held up against the worries and recriminations I was poised to hurl.

“A little lost,” he said behind a meek smile that belied deep shame. “Just a little, just sometime.”

That bowed head, those cold-blued hands. I understood that he meant a lot, and all the time.

“My name,” I said quietly. “My age?”

His eyes on me, glassed with tears. “I know you.”

But could not answer. Could tell me nothing but this maze so vast, this tea like ice, Iceland, ichneumon.

* * *

Six months seething in the Home until they called me in, showed me his bedroom like the crime scene it was. Bed disordered, walls defaced. Window flung open. A looseleaf bearing a single scrawl: Sorry.

Below, the cliffs, the sheer drop, the sea. (I’d sprung extra for an oceanview room.)

“Why wasn’t the window locked?” was all I could think to say.

The orderly ducked his head, in this gesture so resemblant of Ba that I didn’t know whether to hug him or box his ears. “He liked to feel the breeze.”

* * *

So—Gone. Dead, presumed. I bit into the sweet flesh of relief, the hard pit of shame.

* * *

But now: “Wake, wakeful.”

So close. “Wales.” One more turn.

“Ba!” I broke into a run, eyes wide open.

There he was, slack-faced, his soiled nightshirt billowing like it was readying for flight. Ba, my same Ba. I’d half-expected a bovine head blooming from his neck.

I gathered him into my arms, all bones and divots and a stench like singed flesh. “How long have—”

“Windward!”

“What?”

He batted at me urgently. “Winery, wineglass!”

Only then did I notice the down spreading across my chest, the feathers sprouting from my neck. From the itch between my shoulder blades the first stubs of—

“Wineglass! Wineskin!”

Wings.

And the burnt smell I’d blamed on Ba: wax melting, cooling, binding the shafts together.

I searched for fear, but found only wonder.

“What am I?”

He looked at me with a clarity I’d long thought gone. “Daughter.”

“Can I fly?”

But already he was fading again, childlike. “Alogical, aloha, alone. All alone.”

“Ba, I…” I knelt before him, suddenly overcome. “I’m sorry it took so long.”

“Fly, fly,” he said in the cadence of there, there.

He patted my arms, my plume, my lifting wings.

“Zenith,” he said tenderly. “Zephyr. Zero.”

Kathy Chao is a writer and data scientist whose stories have appeared in Strange Horizons, the Kenyon Review, the Georgia Review, and other publications. Originally from Southern California, she now lives in Queens, New York. You can learn more about her work at kathychao.com.

Kathy Chao is a writer and data scientist whose stories have appeared in Strange Horizons, the Kenyon Review, the Georgia Review, and other publications. Originally from Southern California, she now lives in Queens, New York. You can learn more about her work at kathychao.com.