Writers pour so much energy into their craft that sometimes we forget that creative pursuits other than writing can fill us up in other important ways. Here, we’ll look at what writers do when they aren’t writing, and how those pursuits affect the return to the page. This month, we hear from two writers—Mary Morton Cowan and Sarah Parke—about how creative improvisation shows up well beyond the page.

I’ve just completed a writing project. Now what? The first thing I do is clear off my desk. Getting rid of the clutter feels good, and it is satisfying to see the desk’s surface once again. Before I go on another creative writing adventure, I have lots of fun things to do. Maybe I’ll take a walk. I grab my camera, because I know I will see something fascinating that I want to photograph. It takes my mind off writing, but at the same time, it provides more fodder for writing projects. Pictures are fabulous sources for ideas. In fact, I find it hard not to wonder what could be happening behind every scene. No matter what I do to relax from writing, my creative mind won’t stop.

My favorite non-writing activity is playing the piano. I can totally leave my writing somewhere in the back of my brain and enjoy making music. I usually embellish the written score to create a different mood or sound. Playing the piano refreshes me. Knitting and photography are creative activities while accomplishing something, which is important to me. And they are all FUN!

My favorite non-writing activity is playing the piano. I can totally leave my writing somewhere in the back of my brain and enjoy making music. I usually embellish the written score to create a different mood or sound. Playing the piano refreshes me. Knitting and photography are creative activities while accomplishing something, which is important to me. And they are all FUN!

I’m a kid at heart. I write nonfiction and historical fiction for young readers, so my writing brain is eleven years old! I like research—poring through stuff to find fascinating topics that kids will like. Today’s kids cannot imagine what it was like to lay the first transatlantic telegraph cable, or to explore the Arctic, or to live in a lumber camp deep in the woods. I choose topics like these to help kids explore bygone times and adventures. Photographs provide more ideas and they help provide details for describing characters and locations. The fun of writing begins anew when I settle on a new topic. I head for the library, check out a few dozen books to fine tune my focus, and start cluttering my desk again.

Mary Morton Cowan

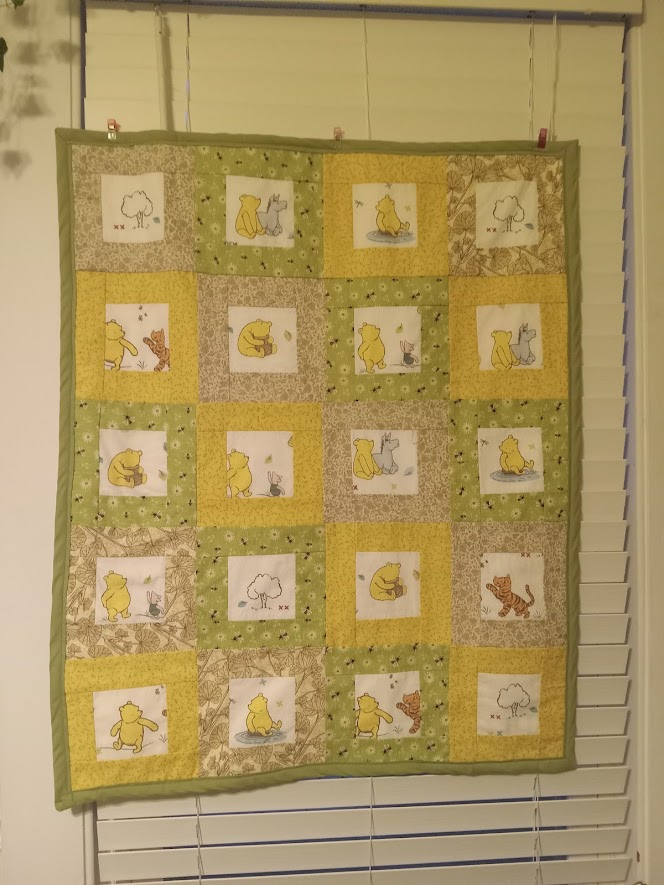

When I’m not writing, I like to spend time on craft hobbies that help me exercise my creative muscles. I refer to this writing avoidance as procraftstination. At different points over the years I’ve gotten into furniture flipping, painting with acrylics, and quilting when the “word well” has run dry. I’ve made three small quilts so far in 2024, and will probably finish another two by the time the year is through. This was also the year I’d set myself an ambitious goal of revising two novel-length manuscripts. I suppose it’s no coincidence that I’m spending more time quilting than ever before.

I learned how to quilt from watching my mom. My favorite part about quilting is picking out the fabrics. I could spend hours wandering my local fabric store touching and comparing all the prints, patterns, and textures. Many of my friends are having babies and I love creating custom baby quilts because they are the perfect size for a weekend project.

In many ways, creating a quilt is like constructing a narrative. For the sake of my metaphor, the fabrics I choose for each quilt project are my characters and setting: they represent aspects of the person receiving the quilt and they need to complement each other in order for the finished design to work. For each project I designate one fabric print as my “main character” (I might pick two if they’re both really appealing), and this fabric is used predominantly in the pieced pattern. The main character fabric is surrounded with three or four more subtle patterns or colors that play “supporting” roles in the larger pattern.

If fabric choices are the characters, the pattern is the plot structure. Like writers, some quilters plan their quilts from the start, while others wing it and see what happens. Traditional pattern piecework quilters use precision-cut pieces and lots of calculation to create intricate fabric mosaics and landscapes. These are the plotters of the quilting world. But there are also “scrappy” quilters–sometimes called “crazy” quilters—who approach piecework in a completely random, pantsing fashion. Think of this method like stream of consciousness quilting where you sew pieces together at random and cut everything to size at the end.

I pursue my quilting the way I pursue my writing: start with a plan and pivot if needed. I spend a lot of time choosing my fabrics (characters), arranging and rearranging the pieces into a pleasing pattern (plot), and then set to work sewing it all together! Though I usually have a general idea of the size and pattern of the quilt when I set out, I’ve learned to adapt when fabrics misbehave or I come up short of material. Sometimes, I’ll realize half-way through a quilt that it’s too busy or complicated and I’ll literally cut out rows or sections like extraneous backstory or subplots in a novel. These setbacks can be frustrating, but visualizing the finished product–and the joy it will bring someone–helps me push through the tough parts of the process.

I pursue my quilting the way I pursue my writing: start with a plan and pivot if needed. I spend a lot of time choosing my fabrics (characters), arranging and rearranging the pieces into a pleasing pattern (plot), and then set to work sewing it all together! Though I usually have a general idea of the size and pattern of the quilt when I set out, I’ve learned to adapt when fabrics misbehave or I come up short of material. Sometimes, I’ll realize half-way through a quilt that it’s too busy or complicated and I’ll literally cut out rows or sections like extraneous backstory or subplots in a novel. These setbacks can be frustrating, but visualizing the finished product–and the joy it will bring someone–helps me push through the tough parts of the process.

See, I told you the metaphor worked!

Sarah Parke

Award-winning author, Mary Morton Cowan, writes for young readers. A Maine native, she graduated from Westbrook High School and Bates College. She has written two award-winning biographies, two historical novels, a logging history, and almost one hundred articles, stories, and activities for children’s magazines, several of which have been reprinted in textbooks and anthologies. She is a member of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators and of Maine Writers & Publishers Alliance. Mary is a visiting author in schools and speaks to a variety of community groups. She and her husband live near Portland, Maine. www.marymortoncowan.com.

Sarah Parke’s short stories have been published in Speculative City and Horrors of the Deep (Rogue Owl Press) and she edited Maine Character Energy: A Charity Anthology (Rogue Owl Press). Her fiction plays with alternate historic timelines and magical circumstances. Earlier in her own timeline, she spent six years helping authors polish their prose as an acquiring editor at a regional trade publisher. She holds an MFA in Popular Fiction from the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast MFA program.

Curated by Jen Dupree