The Masters Review is excited to share the first runner up from our Featured Flash Contest: “The Beak” by Robbie Herbst! In “The Beak,” our thirteen-year-old protagonist finds herself experiencing, as all teens do, a few changes to her body. It all starts in spring, at the kitchen table, with a tooth. Be sure to check back on Friday for our interview with the winner, and stay tuned for our other finalists!

1.

It’s the first day of spring, and she sits at the kitchen table with an underripe orange. She is thirteen and not unlike many of us when we were thirteen—a little shy, a little bold, increasingly wary of the strange and unexpected world we inhabit—when the first tooth falls. She works at the clinging peel, her nail nearly separating as she twists and pries. The flesh is tough and yellow, and after taking the first bite she pauses, considering. What looks like an oddly shaped seed is submerged in translucent tissue. She digs it out, her fingers probing the sharp ivory. Her tongue finds the hole where it recently nuzzled. While she is quick to explain to herself that it is a stubborn, long forgotten baby tooth, another part of her has already accepted it as one of those strange and unexpected things that she will look back on as a portent.

2.

Afterwards, they fall in pairs. Two by two, her teeth leave her as if departing for an ark. They do not wiggle loose, but drip like water off a stalactite. This is aided by the forward thrust of her palate, which seems to be growing outward. It makes her face long, her mouth gaping. She notices their absences when she draws breath, the air playing the gaps like a primitive flute. When she speaks, her consonants are vague and shifting. Words like frown and down and clown merge into a similar phenotype. People listen to this languid, indifferent speech with impatience. What sort of insolence is this?

3.

Now toothless, she can barely speak at all. She tongues her gums as if playing a glissando on a piano. When she sings, her voice is low and pure, unencumbered like the hymns of whales. People do not like to look at her odd, protruding mouth, yet they stare anyway, horrified.

4.

She spends hours in front of the mirror, rotating to observe her profile. There are other changes, too. Her nose is flattening, her eyes shifting to either side of her face. The irises, once a dull copper, have become sharp, glinting topaz. Her neck has grown too, long and elegant. When she sticks her tongue out, it is blue.

5.

Her mother can’t bear it. “When I was your age, I joined the soccer team!” she complains. “When I was your age, I went on three dates with Kurt Blumenstein and he kissed me right on my normal mouth!” She can no longer kiss—her lips are long and brittle. Instead, she approaches her mother and nuzzles her. Her mother sobs.

6.

There are other downsides. She can now understand French. She can now taste subtle flavors on the air—mint and sumac and fresh coriander. When her neighbor plays his cello, the noise is so exquisite that it nearly drives her mad. But no one cares about these things, nor could she describe them if she tried. She is almost six feet tall.

7.

At first it is ruby red—garish. It ages into a pleasant corral, marbled and slender. She runs her hands over it, amazed at the sleek design. Many avoid her now. They are intimidated. It is sharp and fresh, and they suspect that she longs to use it. They are right.

8.

At night, she ventures into the woods. She finds a fir tree and bores a hole in the trunk, her neck moving so quickly that she gets whiplash. She stalks through a stream, bending at the waist to spear a guppy. It doesn’t have much of a taste, only a clean and refreshing sensation as it goes down her throat. She perches on a rocky outcrop, and the night air is warm and vibrant all around her. She can hear the scurrying of field mice, the thrumming wings of a barn owl leaving his roost. She opens her beak, and her trill is clear and piercing for miles in every direction.

9.

It is here that she builds her nest. Her fingers have become long and clever, with grippy pads. She weaves together thistle and sage, boughs of holly trees and a thin silver chain that she finds in the underbrush. She hauls rhododendron branches, the bones of an elk, a pelt of moss that she removes from a beach tree with a single peel. She binds it all with mud from the bottom of a lake. As she applies her mortar, dozens of tiny snails swivel their alien eyes out of the muck in alarm. She pecks open a maple tree, collecting sap in jars, lacquering the walls of her home in a rich, amber hue. She fills the bottom with soft things—a pilfered skein of yarn, wild cotton that she plucks under a slivered moon, a bit of dryer lint that remained in her pocket. It is spacious, warm in the winter months, dry in the rainy season, and it is hers.

10.

She must be careful how she sleeps. When she inclines her head, the beak sometimes pricks the bare skin on her chest. It is never warm. When she passes by clear water, her silhouette describes a creature beyond category.

In the woods around her, naturalists and tabloid journalists stalk in camouflage vests, calling to each other with obsequious hoots. She steps on rocks and through streams so as not to leave tracks. She will not be found, not by the likes of them. She hears them moving in fruitless circles, stumbling and cursing. She laughs—a shrill, musical thing, and it carries to the places where those men scratch their mosquito bites and itch their stubbled faces. They grab their cameras and their rucksacks, tripping over themselves in pursuit. Over long hours, they will chase her mocking echoes for a glimpse, just a glimpse, of her variegated splendor.

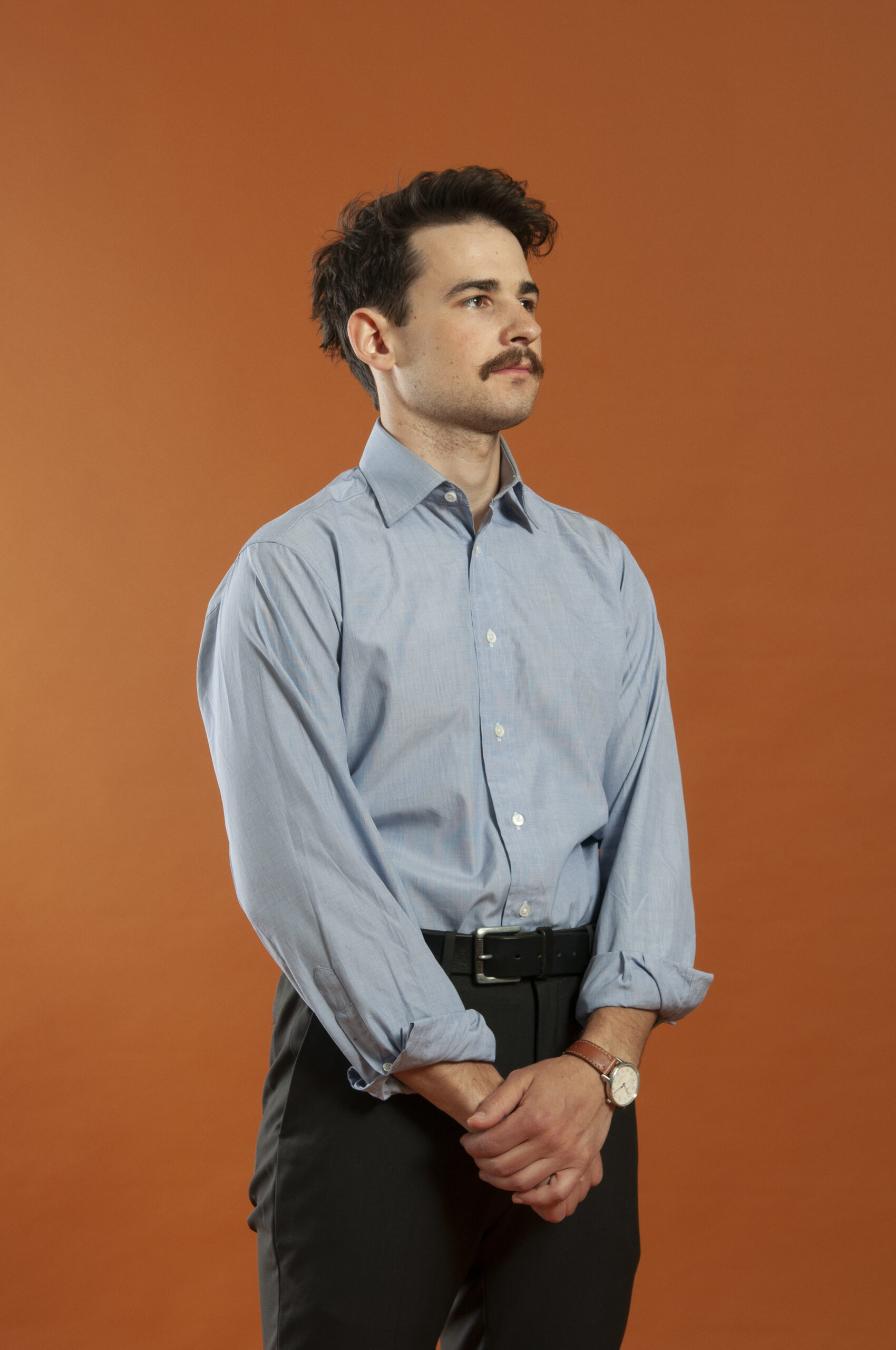

Robbie Herbst is a writer and violinist living in Chicago. You can find his work in The Drift, The Rumpus, Gulf Coast, and other magazines. He’s at work on a novel, and you can read more of his fiction at robbieherbst.com.