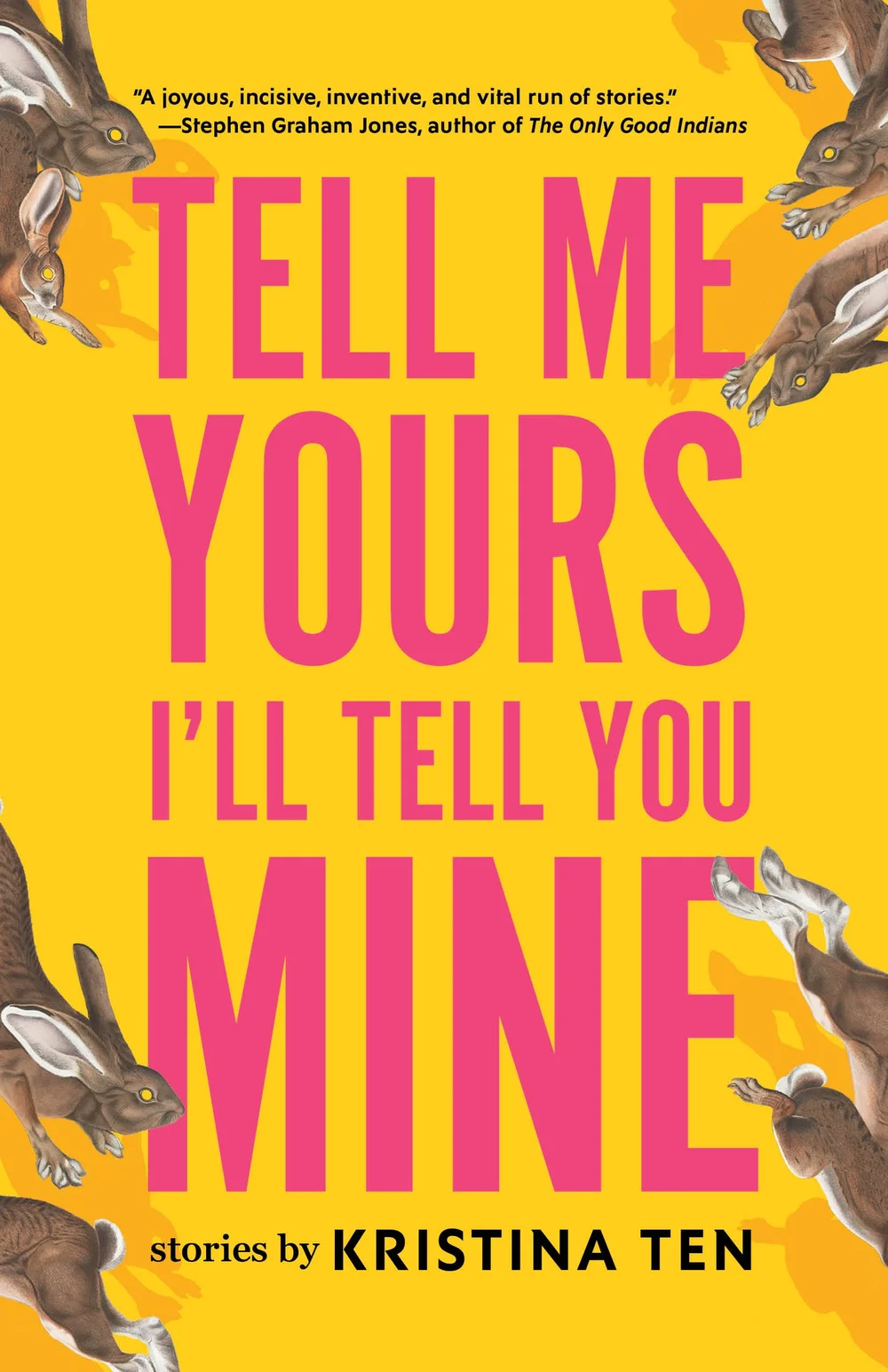

Kristina Ten’s debut speculative short story collection, Tell Me Yours, I’ll Tell You Mine, deals with multiple themes—immigration, oppression, feminism and queerness—but the thread connecting all the stories is the importance of community and our desire, for better or worse, to belong. This affects all Ten’s protagonists from young girls to grown women. Indeed, as the stories progress, the age of the characters increases. This path to adulthood is just as full of cracks and traps as anyone’s. But at any stage in life, the communal forces that push these characters to conform have a terrifying hold over them, the kind of grip that marks and scars.

Kristina Ten’s debut speculative short story collection, Tell Me Yours, I’ll Tell You Mine, deals with multiple themes—immigration, oppression, feminism and queerness—but the thread connecting all the stories is the importance of community and our desire, for better or worse, to belong. This affects all Ten’s protagonists from young girls to grown women. Indeed, as the stories progress, the age of the characters increases. This path to adulthood is just as full of cracks and traps as anyone’s. But at any stage in life, the communal forces that push these characters to conform have a terrifying hold over them, the kind of grip that marks and scars.

The opening stories to the collection focus on childhood. In “The Dizzy Room,” the narrator, the daughter of Russian-Abkhaz immigrants, is forced to play dull educational video games designed to teach English. Everything changes when she gets one in an unmarked box that she calls Dizzy Game: “because that’s how it made [her] feel when [she] played it: queasy and out of breath.” But once the queasiness subsides, her academic and social life skyrocket. Then the game begins teaching her a strange new vocabulary, one that fosters an almost religious obsession in her. She learns words that don’t fit in any other language; words that contain the power to influence people around her; words that separate her from society even when she seems integrated; words she learns not to share with anyone else.

In “The Curing,” a group of middle-schoolers from immigrant families discover that they can use glue to make copies of their body parts. At first, it’s just “something to do.” But then, after making molds of their hands, which they call “spirit hands,” one of the copies moves independently. That obviously doesn’t stop the kids from making more of these “spirit” copies, nor in getting more ambitious in scope. This eerie story of self-discovery is also a reflection on how immigrant children are expected to integrate flawlessly but still remain different and also on what we lose when we’re expected to be several different people at once.

The most chilling portrayal of the adolescent need to belong is in “Bunny Ears.” Hannah’s parents send her to Colden Hills Music Camp. And “for a place with ‘hills’ and ‘music’ right in the name, it’s way too flat and way, way too quiet.” Hanna isn’t particularly interested in music or camp, but that doesn’t change how crippling her desire to fit in with the other campers is.

She’s supposed to have about a hundred things in common with her fellow campers, right, just by virtue of being in exactly the same place and roughly the same age? But then they look at her and every word she’s ever known goes riding off into the sunset of her brain, like, see ya, cowpoke, you’re on your own.

So here’s Hanna, standing between two groups but not really committing to either, holding her arms to her sides hoping nobody notices her ballooning sweat stains, thinking massively boneheaded thoughts like: what if strawberry is just vanilla with a bad case of sunburn?

Poor Hannah. If my last experience at a networking mixer is anything to judge by, I can’t honestly tell her that it gets better. Social butterflies may not understand the lengths that Hannah goes to in order to belong. I won’t spoil it, but it’s shocking. Still, it’s understandable next to the casual, daily mortifications and ever-looming threats of humiliation.

“Mel for Melissa” straddles two age groups. In the form of a therapy journal, the adult narrator writes about her high school volleyball team and its hard-ass coach, a woman that players feared and worshipped. The coach’s motto is “Leave your bodies on the court.” That, on its own, is a banal expression any coach might say to motivate her team. But it works in conjunction with the coach’s strict rules on weight limits and commitment to the team. The piece transforms from a high school sports story to a body horror dealing with the toxic pressure on teenage girls to fit into idealized figures that have nothing to do with health and sport, but everything to do with power and control.

Power and control are also central to the surreal medical story, “The Advocate,” which follows a woman trying to find a doctor who will take the symptoms she’s showing seriously. She envisions each appointment as a joust, and her armor is made of printouts of medical information. It is a metaphor and it isn’t. The injuries she receives from jousting with medical professionals are very real. But I was constantly asking myself if it was the joust or her condition.

In the story “Another Round Again,” Zasha is on a first date in a bar on quiz night. When she discovers her date loves quizzes, she plays along. But as the rounds progress, it turns out that the quiz is all about her. More disturbing, she can’t answer the questions correctly, but her date can.

“Adjective” could technically be called a realist piece, but it expresses the weird in the style rather than character or plot. The protagonist is a naturalized citizen starting her first job and having to deal with the passive-aggressive xenophobia of a colleague. But the story is told in a form resembling a Mad Libs sheet.

Day one at your new job, your coworker wants to know are you really an immigrant.

You brought both passports to HR. You feel ADJECTIVE about that now, but last night you were so nervous about getting it wrong, you PAST-TENSE VERB all the documentation you could think of.

To a certain extent, this drew me into the story. The second person perspective insisted I see myself in the protagonist and the options for completing the sentences gave me an active role in the narrative. It worked with mixed success. It clearly illustrates the impossible social expectations placed on immigrants to adapt to any situation without upsetting the locally born. The style is clever and playful. Also, the blanks evolve with a good dose of the wry humor Ten incorporates into all of her stories. But while my indignation toward the brutish coworker increased as I read, about halfway through I felt like the style put so much emphasis on theme that it hurt the protagonist’s characterization. This story is still a fun read, but it feels less human than other pieces.

It’s not uncommon to hear that, deep down, we’re all the same. This is an idea that can be used to welcome diverse people into a community or demonize members for their differences. Kristina Ten’s wonderfully weird collection, Tell Me Yours, I’ll Tell You Mine, shows these complexities of human interactions and how our drive to belong can lead to isolation. It’s no secret that oppressive power structures are built on our basest fears of non-conformity. Ten’s stories show the consequences of bowing to those fears and allowing the machines of oppression to thrive. They’re also really fun to read. An ambitious debut and an author to watch out for.

Publisher: Stillhouse Press

Publication date: October 7, 2025

Reviewed by David Lewis

David Lewis’s reviews and fiction have appeared or are forthcoming in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Joyland, Barrelhouse, Strange Horizons, The Weird Fiction Review, Ancillary Review of Books, 21st Century Ghost Stories Volume II, The Fish Anthology, Willesden Herald: New Short Stories 9, The Fairlight Book of Short Stories, Paris Lit Up and others. Originally from Oklahoma, he now lives in France with his husband and dog.