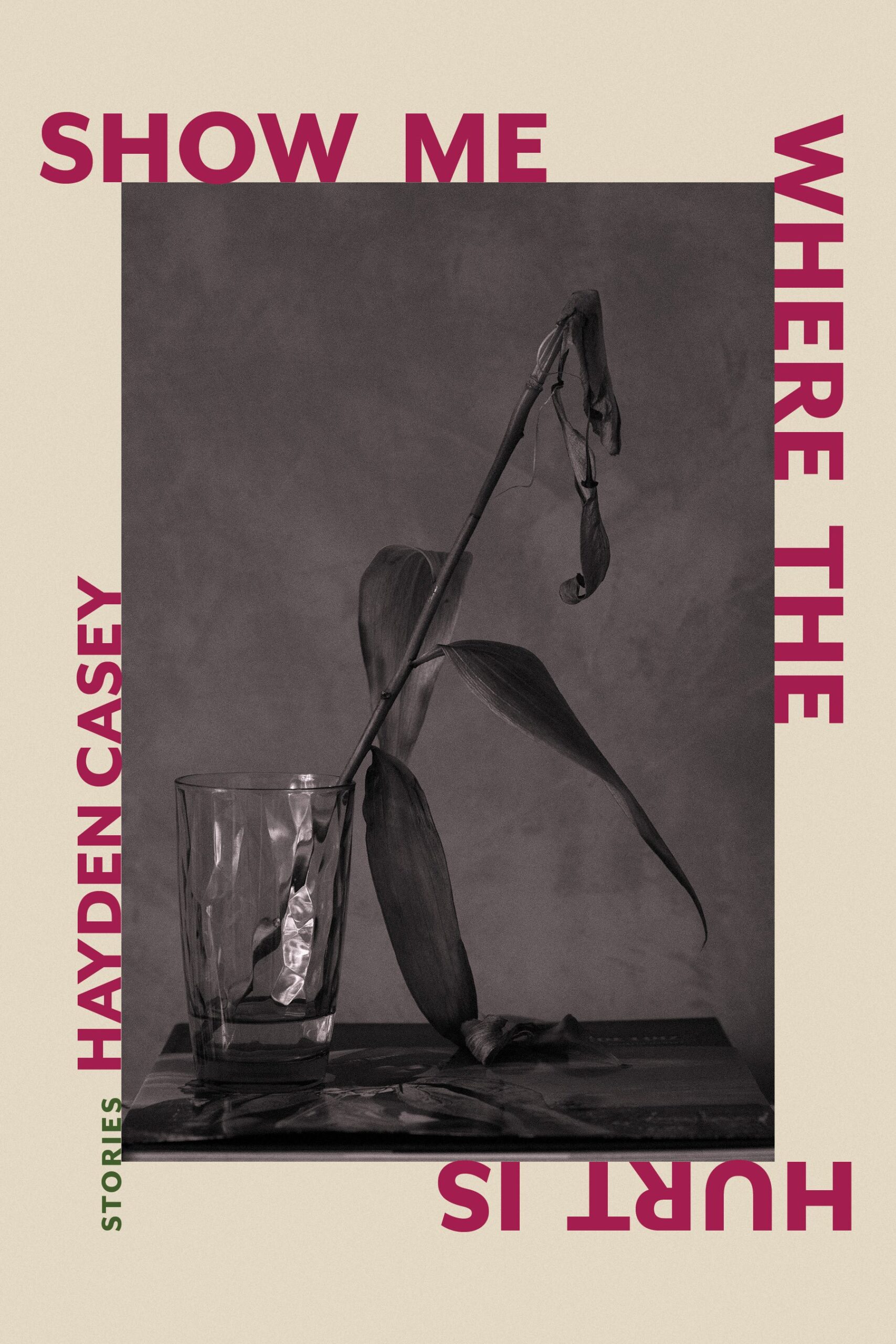

The wounds exposed in Hayden Casey’s debut collection, Show Me Where the Hurt Is, don’t often come with straight forward prognoses. Sometimes these afflictions take the form of strained relationships and the words used to try to suture them back together, or they present with more dire symptoms—starvation, a missing mouth, surreal exchanges of organs. Casey writes characters that are unapologetically vulnerable and positions them as inexperienced yet dutiful guides in the imperfect art of comforting. Through their grief and uncertainty, they manage to forge or fray connections, for better or worse.

The wounds exposed in Hayden Casey’s debut collection, Show Me Where the Hurt Is, don’t often come with straight forward prognoses. Sometimes these afflictions take the form of strained relationships and the words used to try to suture them back together, or they present with more dire symptoms—starvation, a missing mouth, surreal exchanges of organs. Casey writes characters that are unapologetically vulnerable and positions them as inexperienced yet dutiful guides in the imperfect art of comforting. Through their grief and uncertainty, they manage to forge or fray connections, for better or worse.

The collection begins with “Broken Open,” introducing a narrator whose job is to, quite literally, “Be the person your client needs.” Working as an “in-betweener,” her task is to act as a placeholder for intimacy, in this case for Seth, whose girlfriend recently left him. Though in-betweeners are advised against sharing true personal details about their own lives, the narrator is soon talking about her sister, which propels the story into a satisfying slow-burn trajectory of forbidden attachment and misplaced feelings, with an ending that cleverly exposes the chasm between their real and performed identities.

This isn’t the only story where Casey invents a speculative or exaggerated premise that serves as a catalyst to delve into uncomfortable gray areas of characters’ emotional, interior lives, in worlds that are otherwise wholly realistic. The first line of “Bergamot” announces the discovery of a miracle weight loss pill with the words, “They’ve cracked the code, they tell us.” This simple yet deceptive announcement launches the narrator’s relationship, and the world outside, into literal and emotional wreckage. Imagery of carnage backdrops a juncture the couple isn’t able to overcome, conveyed in effectively sparse, questioning language:

How to explain that my entire life has been an exercise in invisibility. How to explain it from beneath his gaze, which I can’t escape. He sees me, he sees me. He says it to me: I see you. As I speak, his thumbs, gentle on my skin, wet lashes fluttering, eyes held to mine. Hours bleed away on that kitchen floor.

“Evergreen” also veers into lightly absurd territory, using the setup of Erin’s boyfriend Ben searching for an unnamed “Something” that’s missing in their relationship and finding it in the short stories she writes, only for him to lose sight of her in the obsession. By the time Ben says, “I’m sorry, but I’m falling in love,” the context of these words is warped beyond recognition, and the moment where their relationship could be salvaged has already passed.

Casey employs a sort of authorial sleight of hand in letting devastating moments like these land even before the reader can detect the point of no return. Tension is held in the delay between discovery and confrontation, in which the main characters must reassess their lives with new knowledge. This is perhaps best played out in “Evidentiary,” which finds a wife in the crux of piecing together her husband’s affair, but the confrontation is so stalled that in the aftermath of this realization, a transformation in her occurs with each new detail of the mistress she gleans.

“Smoothing” (which made The Masters Review’s 2023 Spring Small Fiction Awards Shortlist) takes the concept of transformation to a new plane, in which a fiancé wakes up with his mouth missing the morning after a big fight with his partner. So does “Pretty Things,” with a visceral transposition of body parts, tracing the emotional undoing and reconstruction of the self in a very literal way as Miranda’s roommate Sophie notices her boyfriend’s thumb sprouting in place of her own. But as much as it’s a story of losing oneself to a new relationship and the body horror-tinged love triangle this devolves into, it’s arguably more about navigating the perplexing (and perhaps more interesting) terrain of friendship, with Miranda constantly trying to frame herself and her social status in the eyes of Sophie:

And it wasn’t that I wanted, in the beginning, to be her best friend: I perceived, as anyone would, an immediate distance between us in the social hierarchy, felt the remnants of who we were as high schoolers shining through our skins. We were, and had always been, different girls—I understood myself as her marginalia.

Casey exhibits range in the types of entanglements explored—companionable, familial, romantic, and the fringes of all of these—which is what makes each story in this collection feel fresh, with something new to say in the prevailing thread of repairing brokenness. The college-aged roommates in “Hot Yoga” are tethered to one another by the memory of a deceased third roommate, a brother and best friend, respectively, but when new grief enters Matteo’s life, the narrator finds herself at a loss for how to comfort him. By the time her own feelings for him come into focus, Matteo is already slipping down another path.

In many stories, there’s a fixation on small physical attributes—teeth, moles, skin, hair follicles—that sometimes take on magical realism qualities, or very nearly do. Casey has a knack for illustrating the insidiousness of everyday danger in a way that feels almost folkloric in “Night Swimming,” where the unnamed boys are characterized the way a pack of wolves in a fairy tale might be, by the way they lurk in the peripheries of the girls’ lives with their slippery intentions. The narrator, not fully lucid, repeatedly sees teeth missing from the faces of her loved ones.

“Headache,” which appears just before “Night Swimming,” reads almost like a companion story to it, with parallels in the return of a sibling to a household that’s been upended in some way since the older one’s exodus. While the latter sees the sisters’ father stepping out, in “Headache,” the brothers are grappling with the loss of their dad, and a family history of mysterious headaches that precede untimely deaths. As the older brother slips back into the younger one’s life in a moment of crisis, this line, which comes from such a raw, earnest space, epitomizes a prevailing (though often unspoken) sentiment in this collection: “I don’t know how to say what I’m feeling, but I know how to be here. I know how to try. I had to warm the muscles back up, remind them of their functions.”

Finally, “What is the Nature of the Dance Called Memory” charts the ebb and flow of feelings through light and shadows. It’s an abstract but effective closing story, revisiting the suggestion that “a wound gives off its own light” from an Ann Carson quote teased in the epigraph.

Most of the collection’s strongest notes are in the longer-form stories that allow space for Casey to masterfully drop all the strange and lovely breadcrumbs of each complicated entanglement and contort them into a surprising shape by the end. Shorter, more condensed and immediate works like “Is This It” certainly resonate, too.

There’s an almost timeless, placeless nature to the settings of these stories, but the salient mood of each touches on the epidemic of loneliness facing this era, with feelings of isolation pervasive even in the most intimate of relationships. These stories read like they’re of our time, despite not being anchored to any specific current events. Many of the main characters are without names, making it easier for the reader to crawl into their skin and reckon with the uncomfortable hitches and lapses in understanding readers may resist acknowledging in their own lives.

Publisher: Split/Lip Press

Publication Date: April 22, 2025

Reviewed by Abbie Lahmers

Abbie Lahmers earned an MFA in fiction from Georgia College and State University and was formerly a managing editor of Arts & Letters. Her fiction has appeared in Flyway: Journal of Writing and Environment, Barnstorm, Pif Magazine, and others, with work upcoming in Allium, A Journal of Poetry & Prose. She lives in Providence, RI, writing and editing for local magazines, camping around New England, and posting about plants and books on Instagram (@fauna.and.fronds).