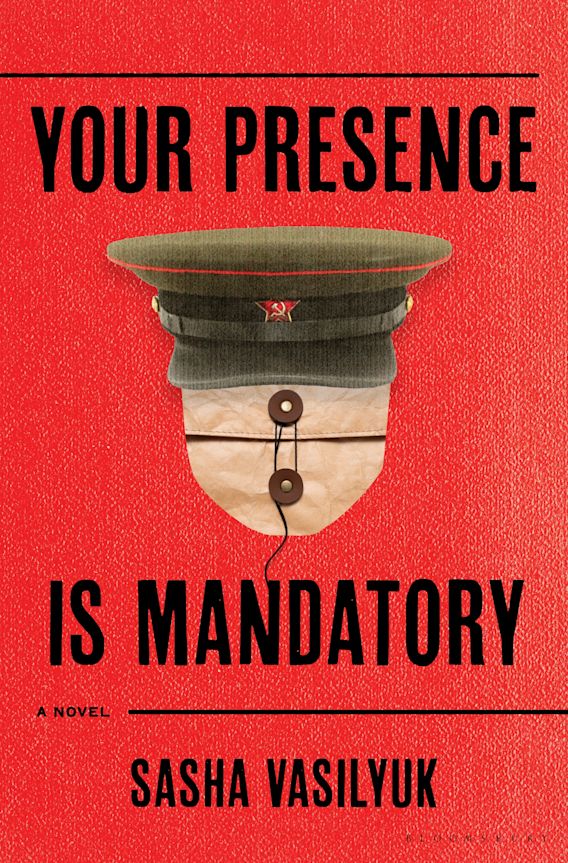

In Sasha Vasilyuk’s debut novel, Your Presence is Mandatory, the Soviet Jew Yefim Shulman fought in WWII only briefly before being captured by the Germans. This POW experience became a stigma he endeavored to hide after the war ended, because the regime he lived under deemed survivors like him Nazi collaborators and thus politically suspect. These two phases of life, war and postwar, unfold in the book as alternating chapters, through which readers witness the war and its ramifications up close. For decades, Yefim kept his POW past all to himself, until a KGB summon forced out of him a confession letter. He was allowed to keep the letter, though, and his family finally learned his secret by discovering this letter after his death. By then, another war was already looming along the Russia-Ukraine border, ready to wreak havoc and tear apart lives.

In Sasha Vasilyuk’s debut novel, Your Presence is Mandatory, the Soviet Jew Yefim Shulman fought in WWII only briefly before being captured by the Germans. This POW experience became a stigma he endeavored to hide after the war ended, because the regime he lived under deemed survivors like him Nazi collaborators and thus politically suspect. These two phases of life, war and postwar, unfold in the book as alternating chapters, through which readers witness the war and its ramifications up close. For decades, Yefim kept his POW past all to himself, until a KGB summon forced out of him a confession letter. He was allowed to keep the letter, though, and his family finally learned his secret by discovering this letter after his death. By then, another war was already looming along the Russia-Ukraine border, ready to wreak havoc and tear apart lives.

The novel’s 300 pages I finished in one day. Many factors contributed to the draw. The chapters, each about only twenty pages long, alternate between the war and postwar years to sustain tense pacing, with the attendant point-of-view shifts between different family members bringing in the broader contexts. By making Yefim, a Ukrainian Jew and a POW, the protagonist, Vasilyuk provides a voice to a one million-strong group who had lived silently on the margin of postwar Soviet society—those whose wartime experiences were incongruous with the state’s narrative of triumph. Yefim’s wartime journey, spanning Ukraine, Lithuania, Poland, Germany, and back home, introduces the readers to a diverse cast of uncommon characters: Lithuanian partisans fighting Soviet occupation, Ostarbeiter (eastern workers) sold to German households as slaves, and German villagers fleeing the Berlin-bound Red Army. Following Yefim’s close third-person point-of-view, we bear witness to his changing subjectivity as a Soviet man: the youthful belief in revolutionary ideology and the subsequent disillusion, the first decision to survive the war and the consequential ones to keep that survival a secret. This journey of life, rendered experience-near through details and well-placed historical information, anchors the novel firmly on the ground of believability. The reference to the Nazi troop as “Fritzes,” for example, recalls Joseph Brodsky’s observation: “[i]n spite of all the good reasons that we had to hate the Germans … we habitually called them ‘Fritzes’ rather than ‘Fascists’ or ‘Hitlerites.’” Certain moments in the novel read like a dramatized nonfiction of a family saga, where Yefim and his family are real people vouchsafing their experiences to posterity to keep their memories alive.

But the real draw of the novel, in my opinion, is the human condition it chooses to zero in on: the weight of pivotal life decisions and their profound moral consequences. “Your presence is mandatory!” The KGB summon resonates with Kant’s categorical imperative: One must follow the demand of a rational moral rule free from any desire or end. In Yefim’s case, surviving the postwar decades meant blotting out his wartime survival from everyone else. This decision subsequently placed him under constant pressure from opposite directions: the need to come clean and the consequence of incriminating his family. For over four decades, he had to live with the weight of the decision, his entire life was a struggle to find the impossible safety at the crossroads. He could not bear coming clean to his family until the very end of his life; the exposure, taking the form of a KGB confession letter, had to wait until after his demise, when the Soviet regime was history and the war itself on the verge of oblivion from the collective memory.

Most of the novel’s readers do not live under a regime that punishes survival. Yet, in the democracy with an individualist culture, private property, and monogamy that they likely dwell in, the institutional setting still offers a set of moral parameters they must operate by. The real-life operation of morality is seldom as mathematics-like as in Kantian deontology, as tremors, negotiations, and conditionals define the lived experiences of ethics. It is the moral weight of choices being lived through that elevates Vasilyuk’s novel above its peers, giving the debut historical depth and poignancy that touch the core of the human condition.

Publisher: Bloomsbury

Publication date: April 23, 2024

Reviewed by Hantian Zhang

Hantian Zhang is a National Book Critics Circle 2023-2024 Emerging Critics Fellow. His writing has appeared in Prairie Schooner, AGNI, The Offing, and elsewhere.